These pages came about as the result of an enquiry in November 2000 from Margaret Beard in New Zealand concerning the Parish Boundaries for Bedminster.

The City Boundaries

Bristol, having always straddled the counties of Somerset and Gloucester was really part of neither, all legal affairs had to conducted in either Ilchester in Somerset or Gloucester. The officials of the town petitioned the King that it become a county in it's own right. Edward III agreed to this a granted the town it's Royal Charter in 1373. The Charter gave the town extensive powers, these included that the Mayor become a royal official and as such have the right to have a sword of state bourne before him. Both he and the Sheriff were entitled to hold courts, thus saving the difficult and expensive trips to Illchester or Gloucester. A council of the 'better and more honest men' was to be elected to assess taxes.

Much of the Bristol Charters 1155 - 1373 is to do with taxes and trade but then on August 8, 1373 comes this:

We, at the supplication of our beloved Mayor and commonalty of the town aforesaid, truly asserting the same town to be situate partly in the County of Gloucester and partly in the County of Somerset ; and although the town aforesaid from the towns of Gloucester and Ilchester, where the county-courts, assizes, juries and inquisitions are taken before our Justices and other Ministers in the Counties aforesaid, is distant by thirty leagues of a way deep in winter time especially and perilous to travellers, the burgesses, nevertheless, of the said town of Bristol are on many occasions bound to be present at the holding of the county courts and at the taking of the assizes, juries and inquisitions aforesaid, by which they are sometimes prevented from paying attention to the management of their shipping and merchandise, to the lowering of their estate and the manifest impoverishment of the same town. Willing for the improvement of the said town of Bristol and also in consideration of the good behaviour of the said burgesses towards us and of their good service given us in times past by their shipping and other things and for six hundred marks which they have paid to us ourselves into our Chamber, of which we will that no one be charged towards us, to provide more amply and abundantly for the said burgesses and their heirs and successors conveniently and quietly, of our special grace, by the deliberation and assent of the learned men of our council assisting us, we have granted and by this our charter have confirmed for us and our heirs to the said burgesses and their heirs and successors for ever, that the said town of Bristol with its suburbs and the precinct of the same according to the limits and bounds, as they are limited, shall be separated henceforth from the said Counties of Gloucester and Somerset equally and in all things exempt, as well by land as by water, and that it shall be a County by itself and be called the County of Bristol for ever.

On September 30, 1373 another charter was issued saying that John, Bishop of Bath and Wells; William, Bishop of Worcester, Walter, Abbot of Glastonbury and Nicholas, Abbot of Cirencester, along with Edmund Clyvedon, Richard de Acton, Theobald Gorges, Henry Percehay, Walter Clopton, John Serjaunt, the Sheriffs Gloucestershire and Somerset, the Mayor of Bristol were to perambulate the boundaries of the county. To attend or swear on oath that the boundaries were correct were Robert Cheddre, Walter Frompton, Walter Derby, Elias Spelly, Richard Bromdon, William Coumbe, John Hakeston, senior. William Wodeford, William Somerwill, John Vyel (who was to become the first Sheriff of Bristol), Henry Vyel, and John Somerwell of Bristol. As well as Ralph Waleys, John Crook, John de Weston, junior, John Kent de Wyke, Robert atte Hay, John Werkesberwe, Laurence Campe, John Wykwyke, William atte Mulle, Robert Tollare, Thomas Overnon and Thomas atte Hethe of Gloucestershire. Also John Beket, Walter Laurencz, William Sambrok, Simon Draycote, John Babynton, Richard Calweton, Richard Oldemuxen, Richard Theyn de Asshton, Richard English, Thomas atte Mulle, Richard Neel and John Artur of Somerset.

The exact route of the perambulation is given in the charter.

With the issuing of this charter the boundaries and the government of the town was fixed up to the Municipal Reform Act of 1835, 450 years later. The posts of Mayor and

Councilors ended up in the hands of the merchants, who tended to fill any vacancies for the various posts with their own nominees. Even so, this Charter was very important to the city and it was with great pride we celebrated the 600th anniversary of the granting of it in 1973.

Evening Post Bristol 600 program cover

Volume LVI of the 1867 - 1868 Parliamentary Papers descibe Bristol as consisting of 22 parishes, and parts of the parishes of Bedminster and Westbury-on-Trym. It goes to descibe the boundary:

From the point on the north-east of the city at which the eastern boundary of the out-parish of St. Paul meets the north-western boundary of the out-parish of St. Philip and Jacob, eastward, along the boundary of the parish of St. Philip and Jacob to that point thereof which is nearest to the point at which the Wells-road leaves the Bath-road; thence in a straight line to the said point at which the Wells-road leaves the Bath—road; thence along the Wells—road to the Knowle Turnpike-gate; thence along the road which leads from the Knowle Turnpike-gate to Bedminster Church to the point at which the same is crossed by Bedminster-brook; thence along Bedminster-brook to the point at which the same crosses the road from Locks-mill to Bedminster; thence along the last-mentioned road, passing the southern extremity of the village of Bedminster, to the point at which the same meets the brook at Marsh-pit; thence along the last-mentioned brook to the point at which the same meets the boundary of the parish of Clifton; thence, northward, along the boundary of the parish of Clifton to the boundary stone marked (C. P.) and (W. P.) 12, marking the north-eastern angle of the boundary of the parish of Clifton, and situate on Durdham Down, east of the Shirehampton-road; thence in a straight line to the southernmost point at which the boundary of the tything of Stoke Bishop meets Parry's—lane; thence, eastward, along the boundary of the tvthing of Stoke Bishop to the point at which the same joins the boundary of the out-parish of St. Paul; thence, northward, along the boundary of the out-parish of St. Paul to the point first described.

The plan before the parliamentary committee was to include portions of six adjoining parishes, Westbury-on-Trym, Horfield, Stapleton, St. George, in Gloucester.hire, Brislington and Bedminster.

The population in 1861 was 154,093 living in 23,590 dwellings with just 11,303 registed to vote.

The Parish Boundaries

All over Britain can be found, if you know where to look, the old Parish Boundary markers. They may be of metal or stone and set into walls or simple markers in the ground. At the time they were erected, when the church played a very much more important part in people's lives than it does now, they helped shape the pattern of your life, the taxes you paid and to whom.

The parish bore the responsibility of looking after its poor. Even when they died the parish performed the last earthly act for them and had to bury them. The parish officers were responsible for distributing the Poor Relief, to ease the burden on their funds they made sure that vagrants were moved on. They were especially keen that

the children of the vagrants were not born in the parish as these children could claim the right of settlement and the poor relief could be claimed for them.

These itinerants became a major problem for most parishes, and not just in Bristol. In the mid 1700's ships travelling to Ireland had to return one Irish vagrant for every seven tons of load they carried. This movement wasn't all one way, around 6,500 people were returned to Bristol from Middlesex between 1808 and 1820.

In 1555, the parishes were ordered to maintain their own roads. The Act stated that every parish should elect two surveyors or waywards who had the power to force parishoners to work on road repairs. The parishoners were expected to work eight hour days for four consecutive days of the year. The more well-off were to provide a

horse and cart as well as the labour. This system was obviously open to abuse, and if they could afford it, people could "buy off" their time. This system of forced labour was replaced in the 1600's to a contribution to the Parish Rate.

The first national Poor Laws can be traced back to 1572 when Elizabeth I was on the throne. In 1576, the compulsion was imposed on local authorities to provide raw materials to give work to the unemployed. The Statute of 1601 compelled the Overseers of the Poor in every parish to buy "a convenient stock of flax, hemp, wool, thread, iron and other stuff to set the poor to work" and to provide for the needy of the parish. But even before this, in 1548, there is an entry in the accounts of St Ewen's church for "Bread and ale to poore people vjd. [5 shillings]"

In the 17th century, burglery, horse stealing and theft of items over the value of five shillings all carried the penalty of hanging. In 1699 the scheme popularly known as the Tyburn Ticket was instigated. On apprehension of a criminal committed for a capital offence, the person that apprehended them would be exempt from local dues in

the parish that the offence took place for life.

These Tyburn Tickets could be transferred once, this usually meant that they were sold. The Bristol Journal contains several advertisments for these tickets. There is one in the issue for 4th September 1813. They usually sold for around £10 - £25 but the Stamford Mecury of 27th March 1818 announced the sale of one of these tickets for £280.

The Poor Rate system proved very expensive to administer and some parishes were in danger of becoming bankrupt. In 1803 the parish of St John's, Bedminster was giving £891 in Poor Relief, by 1831 this had risen to £3,488. This increase was causing problems for the church and the parishoners who had to pay the Poor Rates, as in 1830 to try and shame the people who received the Rates their names and occupations were posted on the church door. By this time many people expected this money as a right and so this public "shaming" of them had no effect. To try and remedy the situation in 1834 the Poor Law Amendment was passed. This had the effect of leaving us the nasty after-taste of the Victorian workhouse.

The 1834 Poor Law Ammendment stated that:

- No able-bodied person was to receive money or other help from the Poor Law authorities except in a workhouse.

- Conditions in workhouses were to be made very harsh to discourage people from wanting to receive help.

- Workhouses were to be built in every parish or, if parishes were too small, in unions of parishes.

- Ratepayers in each parish or union had to elect a Board of Guardians to supervise the workhouse, to collect the Poor Rate and to send reports to the Central Poor Law Commission.

- The three man Central Poor Law Commission would be appointed by the government and would be responsible for supervising the Amendment Act throughout the country

The idea of these amendments was that they would:-

- Reduce the cost of looking after the poor

- Take beggars off the streets

- Encourage poor people to work hard to support themselves.

Chapter 7 of Henry Hazlitt's 1973 The Conquest of Poverty explores the Poor Laws in much more detail.

The Workhouse (Internet Archive) includes a history of Bristol's workhouses (look under both Somerset and Gloucestershire) and contains more information on the Poor Laws.

Map of Bristol's Earliest Parishes

The map was re-drawn from the one that appears in "A Survey of Parish Boundary Markers and Stones for Eleven of the Ancient Bristol Parishes" published by the Temple Local History Group in 1986.

1) St John the Baptist 2) Christchurch 3) St Ewen's

4) St Werburgh's 5) St Leonard's 6) All Saints 7) St Mary Le Port,

Of these parish churches, St. Augustine's, St. Mary Le Port's, St Peter's and St. Thomas's (Temple Parish) were blitzed in 1940, the ruins of St Peter's still remain on Castle Green as does St Mary's. The ruins of St. Thomas's with its leaning tower are still to be seen just off of Victoria Street. St. Ewen's was demolished in 1788. St. Werburghs was moved to a district that was named after it in 1876.

St. Leonard's church stood in Corn Street on the corner with St Nicholas Street. In 1768, the parish was joined with St. Nicholas and the church demolished in 1771 when the Clare Street was built. One of the altars was sold to Backwell Church, Somerset. The vicars of St. Leonard's held an import office between 1615 and 1774 - that of City Librarian. St Leonard's library was the forerunner of the Kings Street Library founded by Robert Redwood in 1615.

A little north of the areas covered here, St. Matthew's did a great job of tracing their parish boundary in Kingsdown and Redlandy (Internet Archive).

Many of the parish markers can still be seen in the area around Corn Street. Other districts around Bristol also contain the remnants of these markers, but because these were simple stone markers these have now largely weathered away. Other districts, such as Bedminster, were largely rural and so used local landmarks as their markers. Many, many other parish markers have now just simply disappeared and no trace of them can be seen. In 2001, I photographed all the markers that I could find:

According to the Survey of Parish Boundary Markers and Stones by the Temple Local History Group the St Leonard's 23 marker was, in 1986, covered with cast iron letters "STL 32". This seems to make sense as on the same building is the marker for STL 33. Perhaps the original stone masons made a mistake or, more likely, the boundaries were changed at sometime. Over the years this sometimes did happen, and is the reason some markers have "A" or "B" on them.

Because of the importance of these boundaries there was an annual peramulation around them. Young boys were thrashed on the markers and girls bounced on them to try and make them remember them.

In Bedminster, on 26th July 1832 a poster was put up, it read:

Notice is hereby given,

that the Churchwarden and Overseers of the Parish

of Bedminster intend

PERAMULATING

The Boundary intersecting the

Parish of Bedminster

Prescribed by an Act of Parliament,

made and passed in the Third Year of

the Reign of King William IV, which

subdivides the EASTERN DIVISION

of the COUNTY of SOMERSET from

the City & County of the City of Bristol.

The Division in Reference to the

Parish of Bedminster

is as follows:-

"Along the Boundary of the Parish of St. Philip and

Jacob to that point thereof which is nearest to the point at

which the Wells Road leaves the Bath Road; thence in a

straight line to the said point at which the Wells Road

leaves the Bath Road; thence along the Wells Road to the

Knowle Turnpike Gate to Bedminster Church, to

the point at which the same is crossed by Bedminster Brook;

thence along Bedminster Brook to the point at which the

same crosses the Road from Lock's Mill to Bedminster;

thence along the last-mentioned Road, passing to the Southern

extremity of the Village of Bedminster, the the point at

which the same meets the Brook at Marsh Pit; thence

along the last-mentioned Brook to the point at which the

same meets the Boundary of the Parish of Clifton."

The part of "point at which the Wells Road leaves the Bath Road" is mentioned twice in the original poster. "The Third Year of the Reign of King William IV" would be in 1830.

With time the parish boundaries would change. St. Mary Redcliffe and St. Thomas, for example, were originally daughter parishes of St. John, Bedminster. They finally became detached and managed their own affairs in 1852.

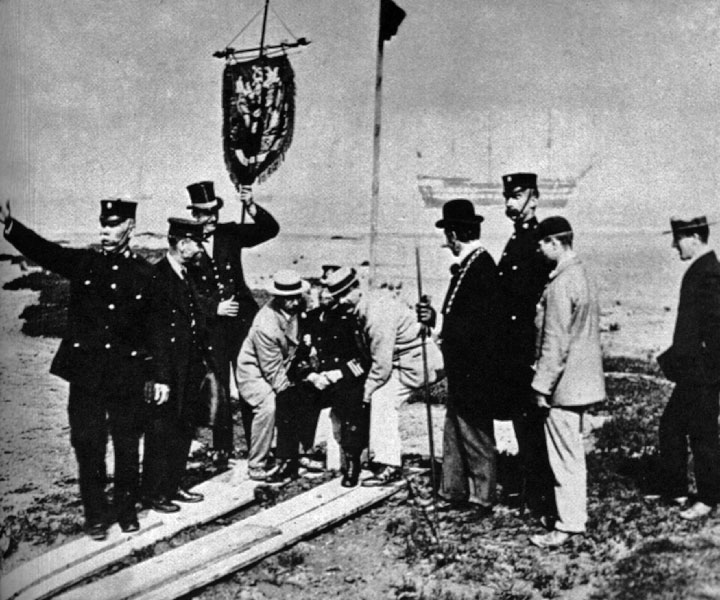

As well as the parish, the city boundaries were also perambulated. The last time this was done was in 1900. Here's a description of it :-

The peramulation of the City boundaries, considered to be essential . . . was commenced on September 10th when about one hundred gentlemen, members and officers of the Corporation met near the bottom of St. Vincent's Rocks, where three hundred policemen with trumpeters and banner bearers already assembled . . . On reaching Purdown after a five mile march, they halted for luncheon. The day's peramulation finished at the Frenchay road where tea was provided . . . The proceedings resumed on the 12th . . . and a halt was called at Magpie Bottom. On the 13th the peramulation was resumed at the same spot, much of the day's journey being over somewhat difficult country, interspaced with water-cress beds, marshes, orchards and gardens. The Avon was reached near Conham, whence two steam vessels conveyed the visitors to Hanham Weir, the eastern extremity of the river jurisdiction. Luncheon was provided at Hanham Court, and after a brief rest the company returned to Conham by water, climbed the steep bank on the Somerset shore and made for St. Anne's Park

and Brislington.

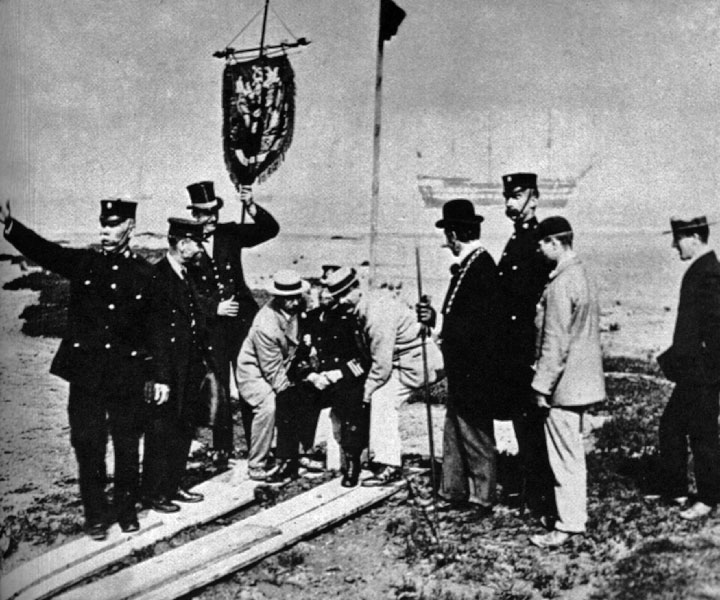

Bumping the Bounds around 1900

The 1900 perambulation lasted a fortnight and was aimed to convince people in the newly absorbed communities that they were now part of Bristol. Starting at St. Vincent Rock, Clifton they walked to the Downs, along Parry's Lane to Westbury and on to Horfield. Moving on to Purdown they called on the Dowager Duchess of Beaufort at Dower

House where the Lord High Steward and the Lord Mayor were "bumped". After this little ceremony they moved to Frenchay, along the Frome to Downend, then Staple Hill and Kingswood.

From Kingswood they walked through the marshy Magpie Bottom then onto Conham where they caught a steamer to Hanham Weir. From then it was back to feet to get to Brislington, St. Anne's, Bedminster, Bedminster Down, Bishopsworth and Rownham. On the 15th day, 250 people got on the steamer Britannia to survey the water boundaries. Starting at Rownham they landed at Shirehampton, then on to Steep Holm and Flat Holm. At both islands iron stakes were hammered into the ground to confirm Bristol's claim to them.

On the way these people didn't let any obstacles stand in their way. Houses lying on the boundary were climbed over using ladders, or people just walked through them. Some of the perambulators became rowdy with a crowd of young women acting as the bumpers who "dealt vigorously" with many of the walkers, including women and

children.

I have produced a Google map showing the parish boundary markers that can still be found - Parish Boundaries of Bristol.

The map was prepared using information from several sources, especially The Temple Local History Group's "A Survey of Parish Boundary Markers and Stones" published in 1994. The converter by Movable Type Scripts was used to convert British National Grid coordinates to WGS84 coordinates which is used by Google maps.

Links

BS24/7 has an article Bristol’s Medieval Parish Boundary Markers Hidden in Plain Sight about the parish boundary markers

Flickr has a whole group dedicated to Parish Boundary Markers, most are about London but there are several about Bristol.

Geograph has a nice collection of Bristol's boundary markers

Boundary Stones in Bristol on Wikimedia Commons

This page created April 15, 2001; last modified July 19, 2022