Bristol - Norman Times

King Henry I, who ruled from 1100 to 1135, made his Barons promise that his daughter, Maud, should be crowned Queen when he died. When he did die, Maud's cousin Stephen usurped the Crown. In the eyes of the Barons this was a good thing and so they did nothing. The Barons seized the opportunity of a divided monarchy to build themselves more castles, wage war on each other and generally oppress the people. Things got so bad that it was said that "Christ and His Saints slept".

David I of Scotland, Maud's uncle, tried to come to her aid, but was defeated in 1138. The same year Stephen decided to reduce the power of Robert of Gloucester (he who had made Bristol Castle one of the strongest in the country) who was half brother to Maud. Robert of Gloucester was in Normandy at the time but immediately sided with Maud and sent a message of defiance to Stephen.

Stephen then seized all of Robert's property, with the exception of Bristol, which proved too strong for him. Bristol gathered together an army of mercenaries and these laid waste to most of the surrounding areas. The time was known as the "Bristol War". Many people captured by raiding parties from Bristol, if they were rich they were ransomed, if not, they were sold as slaves - usually to the Irish. The trade in slaves had been going on since before the introduction of Christianity into England, though with it's arrival the trade had been discouraged. Things were so desperate in England at the time that some families sold their children into slavery. To give an idea of how much money could be made, a man was worth as much as six oxen on the open market. One thing about Bristol's merchants, whatever their morals, they were always very good at making money.

Stephen besieged the city but gave up as he couldn't take it - he was to regret this as in 1139 Robert and Maud returned from Normandy and made Bristol their headquarters.

In 1141 Stephen was defeated at Lincoln and brought to Bristol as a prisoner. In the autumn of the same year Robert himself was captured and an exchange of prisoners was arranged. By now England was in a right old mess. There had been wars between the rival factions for the monarchy and between the Barons for more than six years. The

fields had been left untended and people were dying from starvation. In 1147 Robert died, Maud realising the game was up, left the country.

Against this backdrop of near anarchy the beginnings of Bristol Cathedral were being built. It's foundations were started in 1140 and was ready for its dedication in 1146. Robert FitzHardinge was responsible for its foundation and during building work, in 1142, he was made reeve of the town. A reeve was a sort of steward for the

overlord of the town. It didn't start out as a cathedral but as an Abbey of the Black Canons of St. Augustine and was built in the meadows to the west of the town. A slightly fuller history of the Cathedral is given elsewhere on this page.

When she arrived in Bristol, Maud had bought her nine year old son, Henry. The father of the boy was Geoffrey of Anjou who ruled a large area of France. On the death of Geoffrey in 1150, Henry became Count of Anjou and through Maud, his mother, he had a claim to the throne of England. In 1152 he married Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitane. He also returned to England to claim the throne here.

In 1153, Eustace, Stephen's son died. At the Treaty of Wallingford Stephen agreed with Henry that on his death that the Crown should pass to Henry. Stephen died just a year later and Henry of Anjou became Henry II of England. He never forgot the protection that Bristol had given him and in 1155 he granted a Charter to the people of

Bristol, this Charter freed them from all tolls and affirmed their rights as freemen. Anyone trying to levy tolls on the people of Bristol were to be given the hefty fine of £10.

In 1154, Henry II, had given Robert Fitzhardinge the forfeited estate of Roger of Berkeley and he used his new wealth to enlarge and beautify the Abbey. It was around this time that Henry received a mission from the Pope, the Englishman, Adrian IV. The mission was to conquer for the Roman Church, the heretical slave-raiding island of

Ireland. Ireland was converted to Christianity by St Patrick around seven hundred years before but had lapsed more than a little by the middle of the twelth century.

Warring between the several Irish kings made Henry act and in October 1170 he sailed for Ireland from Milford Haven with 500 knights and several thousand archers and men-at-arms. By the New Year the native Irish Kings and Bishops submitted to him and the Catholic Church.

According to an email I received from Graham Turner, for the help that Bristol gave him in this campaign Dublin was given to the Barony of Bristol, this made Bristolians freemen of Dublin. This gives us the right to "reverse goats along a central passage", but I've got to admit this is the only source I've got for this particular piece of information.

Henry set about putting England in order and a period of long needed peace was finally given to the country. Trade increased and Bristol did particularly well. Bristol's harbour was full of ships, the main imports and exports being corn, hides, wine and wool.

But things did not always go well, in 1173 there was a rebellion by some of his Barons who by now had become to be accustumed to doing things their way. These Barons were brutally quashed and William of Gloucester, Lord of Bristol, decided to submit to Henry. Prince John, who was Richard the Lionheart's brother, married one of Williams daughters, Hawisia, and so he became the Lord of Bristol on the death of William.

In 1188 he reaffirmed the rights of the people of Bristol. They were allowed local Courts, thus they no longer had to travel to Gloucester - although only 25 miles away, at this time it was a days travel. The right to freedom from tolls was reaffirmed, they were no longer obliged to grind corn at the lord's mill, they were allowed to marry without the permission of their lords. None but the citizens could buy imported goods within the town and the rights of 'strangers' and foreigners to sell goods within the town was restricted.

Henry II was to reign for 35 years. On Henry's death in 1189 Richard I, Richard the Lionheart, became king.

The Knights Templar

Richard I, who would only reign for ten years, spent most of his time in the Holy Lands fighting the Muslem, Saladin. While he was away his brother, John, ruled England, which was bad news for the English as John was quite a tyrant.

Many of the early Crusaders were poorly trained in warfare, and as a result they suffered very badly against Saladin and his Turks. Two years before his death, Robert of Gloucester, in 1145, set up the Order of the Knights Templar in Bristol, who were also known as the Poor Knights of our Lord. This is why history is so confusing - everyone and everything important had two or three names!

He built for them the oval Temple in Victoria Street, the foundations of which survive. The members of this Order were trained in warfare, and part of their duties was to defend the Temple - hence their name. They also had to take the same vows as the monks of the time - those of Poverty, Chastity and Obedience. A similar order were the Knight's of Saint John, and these had specific duties as regard to the wounded.

Each Templar had to serve three campaigns on land and two on the sea before they were allowed home. By the time they did get home many of the Templars were either sick or wounded and without any possessions and so those Knights who stayed at home provided them with land.

In Bristol, as well as the Temple, Robert of Gloucester also gave them the surrounding land and here they also built a Priory for themselves. The land given them wasn't particularly good, being very marshy, but at that time most of the land outside the city walls was like that. In fact, there are still clues to this in some of the district and street names of modern Bristol, such as Canon's Marsh and Marsh Street. The land given to them has long been built over and a part of it is covered by our main railway station, which is called Temple Meads.

The Templars occupied this land for around 200 years. They had by now become very wealthy and so the Pope ordered their suppression. Our king at the time, Edward II, for some time resisted this order, but in 1312 gave way. The Templars were in Bristol were seized and thrown into the castle dungeons - here most were killed but the Knight's of Saint John did manage to rescue a few.

The Knight's of Saint John took over the Templars land, they demolished the old Temple and built a much finer one, Temple Church. They also drained the marsh. This was built with weak foundations on the marsh which was still being drained. In 1390 and 1397 they made appeals for money to finish the church. The subsidence of the tower

must have occured around this time as they strengthened the foundations and built the remainder of the tower, which was by now about four feet out of true, more upright. The tower was finished around 1460 and contains an internal buttress to help prevent further inclination.That is how Bristol's Temple Church got it's leaning tower. But history wasn't finished with this building yet.

Edward Colston was baptised here but he seems to have no further connection with it. The Weavers' Chapel, dedicated to St Katherine was also situated here. A pre-war book says that the west window was one of the finest in its class and that the church contained many fine 14th century brasses. One dating back to 1396 read "Thou, O Christ, art witness that this stone does not lie here to adorn my body, but that my spirit may be remembered. Ye who pass it, old, middle-aged and young, put up your prayers for me that thus I may be granted hope of pardon."

The north side of the chancel had a lengthy inscription to the prominant Bristol Knight family. Sir Thomas Knight was Member of Parliament in 1693. He hated foreigners and and was a violent persecutor of non-conformists. Hazlitt liked this man who was narrow-minded and who "reeked" of violent and vulgar patriotism. but even he likened Knight's oratorical style to a bear-garden.

Like St. Peter's on Castle Green, Temple Church suffered severe bomb damage during World War II and the main church, although still standing, is now just a roofless, hollow shell.

The leaning tower of Temple Church, Victoria Street

It looks as if it might collapse, but it's been like this since it was built, over 500 years ago.

This photo was taken in July 1981

King John

King Richard returned to England and shortly after dropped dead - mainly because he was hit by a crossbow bolt, and in 1199, his brother, John became King.

King John lived a very lavish lifestyle and the money to pay for it was raised by increased taxes. At this time it was forbidden for Christians to take interest for money lent, but Jews, under the protection of the King were exempt. The increase in trade that England in general and Bristol in particular, were enjoying meant that money had to come from somewhere and the Jews were the people to supply it. Because people resented paying interest to the Jews they were unpopular and so they kept to themselves. In Bristol, the Jewish 'quarter' was by the Quayside between Broad and Small Streets. For the King's protection the Jews had to pay dearly. Due to his lifestyle, King John, was always short of money. When the Jews became reluctant to give him more money he ordered all Jews in the country to be seized and held to ransom. From one Jew in Bristol 10,000 marks were demanded, this is a huge sum and it is commonly held that this was the sum demanded from all the Jews in the town. When the man refused to pay John ordered that one of his teeth be pulled everyday until the sum was paid. The Jew held out for seven days before the money was forthcoming.

Incidentally, Jews were banished from the country by Edward I in 1290.

By now, it wasn't only the Jews who hated King John, the Barons revolted captured London and forced him to sign the Magna Carta. The Barons and people around Bristol stayed loyal to King John, and when Louis of France arrived, in 1216, to help the rebel Barons it was to Bristol that King John returned. He left Bristol to meet Louis

arriving at the Wash where he was killed.

On his death, the Barons didn't need Louis and he was forced to return to France and John's nine year old son became Henry III, being crowned at Gloucester. Henry was grateful to the citizens of Bristol and again reaffirmed the rights of its citizens. He probably also granted them the right to choose their mayor, and the first one

took office in 1216.

The New Frome and Bristol Bridge

The town was becoming prosperous, but this was bringing in problems of its own. Ships were still being unloaded by being left on the mud at low tide by Bristol Bridge. There was nowinsufficient wharfage and the River Frome couldn't be utilised because it still meandered its way through the marshes around the town.

A bold scheme to change the course of the Frome was put into place. The Frome would be diverted from where it started to run around the south of the town and a navigable channel,St. Augustine's Trench, dug so that it ran straight through the marshes to rejoin the Avon near Canon's Marsh. Although under of mile of channel had to be dug, at the time this was a vast undertaking. The population of the town at the time would have been around 5,000 and it would cost, in those days, the gigantic sum of £5,000. It took a Royal Decree by Henry III to get the men who lived around Temple and Redcliffe to help with the work, which started in 1239. The new channel was finally completed, eight years later, in 1247.

Bristol ~ around 1380

Showing the new course of the River Frome and the River Avon Trench

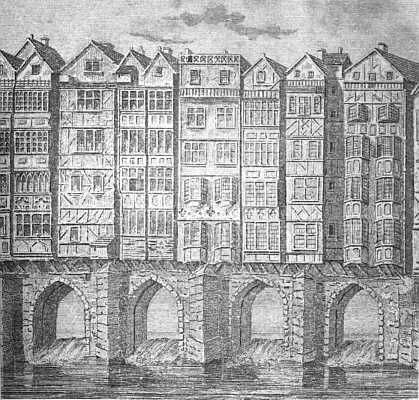

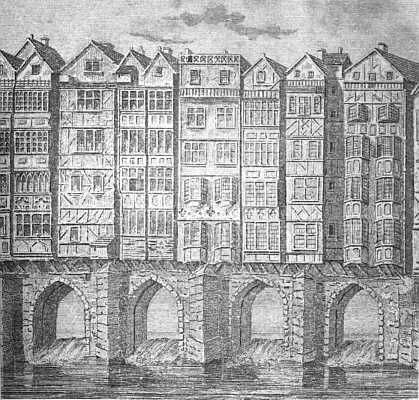

By now Bristol Bridge was in a serious state of disrepair and it was decided to build a new, stone one. This meant building new foundations for the pillars into the river bed. To enable this to be done dams were built at Temple and Redcliffe and a deep trench dug between the two. The Avon was diverted along this trench until the new bridge was finished.

Building started in 1245 and was finished at the same time as the new Frome channel was opened in 1247. The bridge had three massive pillars giving four archways. On top of it was built a double row of houses and across the middle of it was a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary. This bridge was very well built and lasted up to 1768, and even then the pillars were found to be in good enough condition to be kept.

A print of Bristol Bridge in 1247

Bristol Bridge as it is now

These huge building works bought an even larger area into the town and new walls were built to enclose them. This must have been an exciting time for the Bristolians of the period. In the space of a few years the shape of the town had been dramatically changed.

Adams's Chronicles of Bristol has this to say about 1247 :-

This year was the trench digged and made for the river from Gibtailor to the quay by consent of the mayor and commonalty, and as well of and by the consent and charges of the ward of Redcliffe as by the town of Bristoll: before which time the river or fort was at the shambles that now is, and did run round about the castle; and therefore the church Our Lady's Assumption was and is called St. Mary le Port. And this year the bridge of Bristoll began to be founded, and the inhabitants of Redclife, Temple and Thomas were incorporated and combined with the town of Bristow; whereas before it was two towns and two markets kept therein; the one at the High Crosse of Bristow, the other at Staleng Crosse in Tempell Streat. And for the ground on St. Augustine side of the river, it was given and granted unto the commonalty of Bristow by Sir William Bradstone then abbot, for certain money to him paid, and to be yearly paid by the commonalty: as by writings and covenants between them made may appear."

Bristol, because of its shipbuilding heritage, became in the 13th century, Englands main manufacturer of ropes used for seige engines.

The Three Edwards

Peace didn't last long as Henry III proved to be very unpopular and in the spring of 1264 England descended into civil war. Trouble started for Bristol when the people were asked to pay to put the castle in a state of defense. Prince Edward was besieged in the castle, from where he managed to escape. A while later the Prince saw the futility of trying to calm the people and ordered the Governor of the castle to yield to the townsfolk.

A fleet of ships set out from Bristol for Wales to bring Simon de Montford, the main rebel Baron back up the Avon. This fleet suffered severe losses when it was attacked by three of the Prince's galleys, which managed to sink eleven ships from the fleet. This was bad enough for the rebels, but then Bristol castle fell to Royalist forces in 1265. The town was fined £1,000 for it's part in the civil war.

Prince Edward became Edward I in 1272 and his laws and kingship greatly increased trade, Bristol prospered again, for a while anyway. In 1307, Edward's son, another Edward, became Edward II. He was a lot less able than his father and his lavish lifestyle made great demands on the economy. This may sound familiar, the same thing had happened almost exactly 100 years before with King John.

In 1313 Lord Badlesmere, who was the Constable of Bristol castle, demanded in the name of the king, a toll on all fish landed in the port. This caused civil uproar and the townsfolk refused to pay. Their leader was John Taverner. He was one of the people chosen to represent Bristol in Edward I's parliament in 1295 and had been elected

Mayor twice.

A commission of enquiry was set up. Unfortunately, Lord Thomas of Berkeley presided over this. Unfortunately because he was already known to be a Royalist and so were many of the jury. While the judges were in an upstairs room of the Guildhall a meeting was held by some of the townsfolk who were encouraged to resist the enquiry. This they did by attacking the Guildhall, several of the judges broke limbs by leaping from the upstairs windows. In all, 20 men were killed in the fighting.

At this time Bristol was governed by a group of fourteen merchants, who had sided with the King, who now declared the citizens outlaws. The townsfolk drove the group of merchants out of the city and seized their goods. The King's officers were imprisoned and Taverner was appointed Mayor. A new wall was built around Wine Street to protect themselves from the castle.

Early in 1314, Edward II sent an army of 20,000 men to beseige the town with the Earl of Gloucester leading them. They were withdrawn after a short time as they were urgently needed against the Scots, who decisively defeated them at Bannockburn.

A new enquiry into the lawlessness in Bristol was set up in London in March, 1316. Not surprisingly, the people of Bristol were found guilty. The King's cousin, the Earl of Pembroke, was sent to demand their submission. He delivered a message saying that if the ringleaders were given up the rest would be pardoned. The reply from the town was :

We did not begin the strife and we have done no wrong to the king. Certain men tried to deprive us of our rights, and we defended them, as reason was we should. If, therefore, the King will take off the burdens he has laid upon us, and will grant us life and limb, chattels and tenements, then he shall be our lord and we will do his will; if not, we will go on as we have begun, and will defend our liberties and privileges even to the death.

This must have incensed the King as he now determined to end the militancy of Bristol for good. The town was beseiged again and the Lord of Berkeley blockaded the city from the sea. Siege engines installed in the castle threw boulders at the blockades in Wine Street, breaking them down. The town was forced to submit to the King. This bought fines of 4,000 marks to the town as well as arrears of all the duties due to the king. The ringleaders were imprisoned and John Taverner and his son were banished. Strangely enough the rights of the town were restored to it.

1322 saw Edward II have complete victory over his enemies and two of them, Henry Wylington and Henry de Montford, fled to Bristol. Here they were captured and hanged. The bodies of these two men were left on the gibbets until they rotted.

Edward made one of his friends, Hugh Despenser the Younger, Constable of the castle. In 1326 Isabella, the King's wife, landed back in England and marched against him. Bristol declared itself for her but Edward took refuge here and put the elder Despenser, who was nearly ninety, in charge of the castle. Isabella took Gloucester castle then marched south to Bristol. Edward and the younger Despenser escaped by boat, but the elder Despenser was captured. He was hung just outside of the town in his armour, cut to pieces and the bits given to the dogs.

The day the castle surrendered to Isabella in 1327, her son, another Edward, was declared King. Edward II was soon captured and returned to Bristol. From here he was taken to Berkeley, where, on the night of 21st September 1327 he was murdered.

Against these events Adams's Chronicles of Bristol tell us that in 1316 :-

This year was great famine in England, that in many places horse flesh and dogs were counted good meat; and prisoners in some places did kill and eat such as were newly brought in for prisoners: and near the borders of Scotland women were fain to eat their children for scarcity by means of the wars; and after this came a pestilence in England.

Trade, Guilds and the Red Books

Edward III came to the throne and under his rule a new period of prosperity began. England was at this time producing a lot of wool but it was being sent abroad to be finished. To encourage more wool to be worked here Edward set up eleven "Staple" towns, of which Bristol was one, to control its export. This pleased Bristolians as it increased the ports trade but they weren't so happy when foreign weavers arrived here to carry on their trade. They complained to the King who didn't listen to them, which was just as well, as soon Bristol woven Red Cloth was famous.

This trade in wool led to many families taking their surnames from it and so Bristol has many a family named Weaver, Dyer, Tucker, Fuller, Webb, Webber, Taylor and many other derived from working with wool. One famous Bristolian at the time was Thomas Blanket, who was originaly came from Flanders, having arrived here in 1337. He was not well liked by other traders as he didn't belong to a 'Guild', but the King especially excused him. It is often said that he invented the article that bears his name, but blankets were in use around 1200 and it is much more probable that his family took their name from their trade.

At this time all trade was strictly regulated. Anyone wishing to ply a particular trade had to belong to a guild. For instance, someone wanting to become a weaver had to serve a seven year apprenticeship with a Master Weaver. For his part the master weaver had to instruct, feed, clothe and ensure the apprentice attended church. After the

seven years he could become a Journeyman. This meant he could work 'by the day' for a Master Weaver. If he wanted to set up a business himself, he had then to produce a 'Master Piece'. This was examined by the Guild of Weavers. If the work was good enough he could set up in business for himself.

After this he was still not free to do as he pleased. He had to become a member of the Guild of Weavers and attend its meetings regularly. Guilds were usually connected with the church, Bristol weavers had their chapel in Temple Church, where a candle was kept burning to their patron saint. All work that left the business had to tested for width and quality. For any substandard work the Master Weaver was fined, further instances of shoddy work and the weaver could be turned out of the Guild, this meant that he would not be allowed to weave anymore. The Guilds also regulated the price of goods and the number of hours worked.

In 1344, William de Coleford, the Recorder of Bristol, started the Little Red Book which contains the Ordinances or Rules of the Guilds. The later Great Red Book, which was started in 1373, contains records of all land and buildings in the town. When the Little Red Book became full the Ordinances were written in odd spaces in the Great

Red Book. Both books get their names from the red deerskin in which they were bound.

To continue our example about the weavers, the Red Books state that fines were imposed if work was produced that was not of an acceptable width. If the cloth produced did not contain enough threads or was loosely woven, what was called 'tossed', then both the cloth and the loom that produced it were to be burnt. If the quality was not high enough then either a fine was imposed or the cloth and / or the loom was to be burnt. Every maker had to have an identifying mark on his goods, if the mark was not present or worse still, that of another maker used then the weaver was fined.

The most powerful of the Guilds was the Fellowship of Merchants. During the reign of Edward VI (1547 - 1553) when they realised that some of the Ordinances were falling into disuse they obtained a Charter which enabled them to enforce them much more strictly. They also changed their name to the Merchant Venturers of Bristol - an organisation that will figure prominently in Bristol's development.

Most trades are mentioned in the Red Books. At the time bread was sold through women called Hokesteres, these were allowed a penny in the shilling profit. To protect the trade of these women an ordinance made in 1473 said that if these women must be utilised in the selling of bread. The weight, quality and price of bread was controlled, if it did not meet the standards laid down then that bread would be forfeit. As with the weavers the bread must have a makers mark.

Brewers had their own set of rules. They were forbidden to buy grain before the market bell was rung. The water used in brewing had to be drawn from some other place than the public supply. At the sounding of curfew the taverns had to close their doors. All beer on the premises had to be open to official inspection. If the beer was not up to standard then the brewer would forfeit it. Standard measures had to be used, and anyone could call upon witnesses if they thought they were given short measure, in fact every tavern had to provide a flat level area on which measures could be placed.

Following the religious beginnings of many of the Guilds, the Ancient Fraternity of St. John the Baptist was formed in 1392, in 1399 under a charter issued by Richard II, it changed its name to the Ancient Fraternity of Merchant Taylors and finally in the 18th century to the Company of Merchant Tailors. The officials of this Guild were the Master, the Keeper and the Wardens, these were all elected annually. These officials could admit new members but these new members were to be of "goode conversation and honeste", they also had to provide surities of their good faith and promises to keep the ordinances. The guilds had two aims - to maintain the standards of the craft they were employed in and from this uphold the city's honour or reputation in that craft. This is the reason that the city councils assented to the trades being regulated by the Guilds. The Merchant Tailors had their chapel in St. Owen's church. The Guild chaplain would hold prayers daily for the "honour of God and St. John the Baptist". On special days all the Guild members had to attend this chapel, they also had to attend meetings of the Guild to hear "the ordinances read before all the company, that every one of them may better know the ordinances and the meaning of the required oath". Other matters that touched on the members working lives were also discussed at these meetings.

As well as protecting their craft the Guild would also look after those members that had fallen on hard times. Such members would appear before the Guild officials with whatever goods he had. An inventory would be made and the goods returned to the member. On his death the goods would become the property of the Guild but in return if they were single they would be granted 1s a week from the Guild funds, this was in the days when a cow could be bought for 7s, a sheep for 3s and a pig for 4d. If the member was married with children then his goods were divided into thirds. His wife and children would have the value of two thirds, his portion would be rendered up to the Guild and he'd get his pension.

If the hardship was deemed to be the fault of the Guild member then no money from the funds would be forthcoming but the sick and helpless were always provided for. The care provided by the Guild could also extend beyond death. If the member were to die within a ten mile radius of Bristol then the Guild officials could use their funds to bring the body back to the city for a decent burial.

Any attempt by the Guild member to corner supplies or to take advantage of a purchaser then the member would be censured or fined. Persistant offenders could be thrown out of the Guild, this meant he could no longer practice his trade. Even wastefulness was frowned on :-

If any tailor of the said craft lose (or spoil) by his evil working cloth or garment to him delivered to be cut, if the possessor of the said cloth will thereof complain to the master and the wardens and certify by his oath how much the cloth cost him, the costs, if it be found that the said garment may not conveniently serve the possessor and deliverer, shall be fuly given and paid, and the garment shall remain with the tailor as his own goods, and so every tailor shall be better advisedto cut well and efficiently the cloth that is unto him delivered to be cut.

The Mayor was empowered to fine a member 40d from any tailor not belonging to the Guild. Guild members working on Sundays or holidays were also fined, as were those who slandered another tailor.

No tailor was to have more than three apprentices at one time and these apprentices, before being admitted to the Guild, had to satisy the Master and Wardens as to the quality of his work. Whilst one apprentice may have been certified to make coats, ladies garments, hose and doublets another may have been certified to make all manner of men's clothing and nothing else. David Howell for example was not allowed to make any new garments but only repair them.

Increasing competition and the fact that some of the tailors were producing goods not made to order but producing surplus to be sold elsewhere led in 1489 to the following ordinance to be issued :-

From this time forward none within our fellowship shall sell any kind or manner of hose whatever it be, man's or woman's, in the market commonly called the Hie Strat or market place upon bords or tressels or other ways, but in their shops or homes on pain of fines and eventually expulsion from the fellowship.

But, as with other crafts, the rot had started and the Guilds had started to lose control of the crafts. Henry VIII took advantage of the Guilds links with the church to confiscate their funds. The richer Guild members took control of the Guilds, and as the power of the church began to wane, the ordinary Guild members began to lose their rights. The economics of the time meant that the individual worker could be free to compete for work and wages, in reality some merchants had become very wealthy, whilst for others this new freedom for competition become the freedom to starve.

The last surviving member of the Company of Merchant Tailors, Isaac Amos, died in 1824. The property of the Guild, under a scheme of 1849 is held in trust and was used to maintain several pensioners in the Company's Almhouse in Merchant Street. The Tailor's Guild Hall still stands, it can be found in Tailor's Court, just off of Broad Street. This building was built in 1740, replacing an earlier building. Although rather plain looking the portico contains a wonderful moulding of the

Guild's arms.

The Red Books also provide an insight into other parts of life in Bristol at the time. Strangers and foreigners had to assure the officials of their good standing, else they'd be imprisoned or fined, as would anyone harbouring them.

Curfew was rung at St. Nicholas and no one was allowed out at night unless he had a torch - the penalty was imprisonment. Anyone letting dogs off of their chains would be fined. Anyone letting pigs or ducks loose in the town would be fined for the first and second offence. The third time they would lose the animals and they'd be fed to the prisoners in the town jail.

My favourite bits are that no-one was allowed to throw into the street from their premises, either via the door or windows, at any time of the night or day, any urine or 'stynkinge' water or other filth. Imagine what the town must have been like if they had to bring in that piece of legislation. Also, that any lepers were to go and live in Bedminster - some people say they're still there.

The Plague and after

The ordinary houses were built of wood and plaster with roofs of stone or tile. The widest road was only 20ft across. There were no pavements, the stone slabs making up the road way inclined to a central gutter which was litle more than an open sewer. Disease must have been an ever present danger, but in 1348 the Black Death, Bubonic Plague, arrived. While I can find no figures for the number of fatalities, a large proportion of the population must have died as 'the living could scarce bury the dead' and grass was left to grow in Broad and High Streets. Trade more or less stopped.

Geoffrey le Baker, a contemporary cleric of Oxford described the spread of the plague across the land :-

And at first it carried off almost all the inhabitants of the seaports in Dorset, and then those living inland and from there it raged so dreadfully through Devon and Somerset as far as Bristol and then men of Gloucester refused those of Bristol entrance to their country, everyone thinking that the breath of those who lived amongst people who died of the plague was infectious. But at last it attacked Gloucester, yea and Oxford and London, and finally the whole of England so violently that scarce one in ten of either sex was left alive. As the graveyards did not suffice, fields were chosen for the burial of the dead . . . A countless number of common people and a host of monks and

nuns and clerics as well, known to God alone, passed away. It was the young and strong that the plague chiefly attacked . . . This great pestilence, which began at Bristol on 15th August and in London about 29th September, raged for a whole year in England so terribly that it cleared many country villages entirely of every human being.

Around a third of the population of England died of plague that year.

There is an old English nursery rhyme called 'Ring O' Roses' that goes :-

Ring o'ring of roses

A pocket full of posies

Atishoo! Atishoo!

We all fall down

This rhyme is about the plague. The first line refers to the early symptoms, raised red / blackish spots that eventually turn to blisters. A pocket full of posies refers to the fact that sweet smelling flowers were supposed to ward off the 'evil fumes' that caused the disease. Atishoo, atishoo refers to the later symptoms. Bubonic plague affects the respiratory system, and so would cause coughing or sneezing fits. We all fall down is the final death of the victim. Many nursery rhymes were a way of remembering historic events; "Humpty Dumpty" is about an English Civil War seige cannon, "Georgie Porgie" is about King George IV, "Jack and Jill" is about a tax of liquid measures, and so on. The meaning behind these rhymes is fascinating.

There are several 'plague pits' in Bristol, or at least the supposed sites of them. The best known are the ones in Victoria Street and the one under what is now Bentall's department store in Broadmead. However the one in Broadmead is a myth. In 1954, a team of archeologists dug under what was then Magpie Park expecting to find the supposed plague pit. What they found was a series of graves in neat, orderly rows facing east. What was for years thought to be a plague pit was in fact part of St. James's churchyard. Nothing is left now of these sites. In the west of the city just beyond Durdham Downs, towards Stoke Bishop, is the oddly named Pitch and Pay Lane. In days gone by, during times of the plague, people from Bristol were not allowed to leave the city. To obtain fresh food and other goods the townsfolk would gather here and throw money to the vendors on the other side of the lane, who would throw their wares back. This begs the question of who threw first? If the townsfolk threw out their money what would stop unscrupulous merchants picking it up and going on their way? If the merchants threw first, what could they do if the buyer didn't throw the money back? How much money is a trip to a plague infected town worth, especially if once in you weren't allowed out again, given that the death toll was often 30% and as much as 50% of the population? Or perhaps that's just my suspicious mind.

When the plague passed trade began to pick up once more. Men were urgently required for work and the old ways of the Guilds were set aside. Increasing trade meant that the old ordinances were harder to enforce and many of the Jouneymen didn't want to return to the old ways. The Master men grew more influential and by 1500 the old Guilds had become trade companies, only the wealthiest members of which had any influence.

The New Charters - we become a County

In 1347 Edward III gave the town the right to punish 'nightwalkers and dishonest bakers' and to erect a new lock-up to replace the old one, which was falling apart.

In 1346, the English used 738 vessels against the French campaign. Of these, Bristol had provided 24 ships and 608 men. In 1372 it provided another 11 ships to the English fleet.

Bristol, having always straddled the counties of Somerset and Gloucester was really part of neither, all legal affairs had to conducted in either Ilchester in Somerset or Gloucester. The officials of the town petitioned the King that it become a county in it's own right. Edward III agreed to this a granted the town it's Royal Charter in 1373. The Charter gave the town extensive powers, these included that the Mayor become a royal official and as such have the right to have a sword of state bourne before him. Both he and the Sheriff were entitled to hold courts, thus saving the difficult and expensive trips to Illchester or Gloucester. A council of the 'better and more honest men' was to be elected to assess taxes.

Much of the Bristol Charters 1155 - 1373 is to do with taxes and trade but then on August 8, 1373 comes this:

We, at the supplication of our beloved Mayor and commonalty of the town aforesaid, truly asserting the same town to be situate partly in the County of Gloucester and partly in the County of Somerset ; and although the town aforesaid from the towns of Gloucester and Ilchester, where the county-courts, assizes, juries and inquisitions are taken before our Justices and other Ministers in the Counties aforesaid, is distant by thirty leagues of a way deep in winter time especially and perilous to travellers, the burgesses, nevertheless, of the said town of Bristol are on many occasions bound to be present at the holding of the county courts and at the taking of the assizes, juries and inquisitions aforesaid, by which they are sometimes prevented from paying attention to the management of their shipping and merchandise, to the lowering of their estate and the manifest impoverishment of the same town. Willing for the improvement of the said town of Bristol and also in consideration of the good behaviour of the said burgesses towards us and of their good service given us in times past by their shipping and other things and for six hundred marks which they have paid to us ourselves into our Chamber, of which we will that no one be charged towards us, to provide more amply and abundantly for the said burgesses and their heirs and successors conveniently and quietly, of our special grace, by the deliberation and assent of the learned men of our council assisting us, we have granted and by this our charter have confirmed for us and our heirs to the said burgesses and their heirs and successors for ever, that the said town of Bristol with its suburbs and the precinct of the same according to the limits and bounds, as they are limited, shall be separated henceforth from the said Counties of Gloucester and Somerset equally and in all things exempt, as well by land as by water, and that it shall be a County by itself and be called the County of Bristol for ever.

On September 30, 1373 another charter was issued saying that John, Bishop of Bath and Wells; William, Bishop of Worcester, Walter, Abbot of Glastonbury and Nicholas, Abbot of Cirencester, along with Edmund Clyvedon, Richard de Acton, Theobald Gorges, Henry Percehay, Walter Clopton, John Serjaunt, the Sheriffs Gloucestershire and Somerset, the Mayor of Bristol were to perambulate the boundaries of the county. To attend or swear on oath that the boundaries were correct were Robert Cheddre, Walter Frompton, Walter Derby, Elias Spelly, Richard Bromdon, William Coumbe, John Hakeston, senior. William Wodeford, William Somerwill, John Vyel (who was to become the first Sheriff of Bristol), Henry Vyel, and John Somerwell of Bristol. As well as Ralph Waleys, John Crook, John de Weston, junior, John Kent de Wyke, Robert atte Hay, John Werkesberwe, Laurence Campe, John Wykwyke, William atte Mulle, Robert Tollare, Thomas Overnon and Thomas atte Hethe of Gloucestershire. Also John Beket, Walter Laurencz, William Sambrok, Simon Draycote, John Babynton, Richard Calweton, Richard Oldemuxen, Richard Theyn de Asshton, Richard English, Thomas atte Mulle, Richard Neel and John Artur of Somerset.

The exact route of the perambulation is given in the charter.

With the issuing of this charter the boundaries and the government of the town was fixed up to the Municipal Reform Act of 1835, 450 years later. The posts of Mayor and

Councilors ended up in the hands of the merchants, who tended to fill any vacancies for the various posts with their own nominees. Even so, this Charter was very important to the city and it was with great pride we celebrated the 600th anniversary of the granting of it in 1973.

Evening Post Bristol 600 program cover

The Cathedral

Robert FitzHardinge founded the Abbey of the Black Canons of St. Augustine in 1140 in the fields to the west of the town, and it was ready for its dedication in 1146. The abbey was well endowed from its foundation and held benefices in Ireland and South Wales, despite this the abbey was frequently in debt. Abbot Richard was the first abbot and was here for 38 years, the 5th was Abbot David (1216 - 34) who built the Elder Lady Chapel. The running of the abbey was always disorderly, the bishops of Worcester constantly complaining to the abbot. In 1278 Bishop Giffard said of the abbey "damnabilitier prolapsum", which can be translated as being in a state of criminal backsliding.

Between 1306 and 1132 the abbot was Abbot Edmund Knowle who started an extensive rebuilding of the Abbey for it was was falling into disrepair. He rebuilt the choir, aisles, Lady Chapel, Berkeley Chapel and the Sacristy. The Abbey was rebuilt wider than before and with windows that stretched to the roof. This design meant he couldn't use flying buttresses to support the roof, so instead built stone beams inside of it. The design of this makes Bristol Cathedral unique in that it has three aisles all of equal height. But Bishop Cobham in 1320 still had cause to criticise the running of the abbey. Abbot John Snow (1332 - 41) continued the rebuilding. When Bishop de Bransford visited the abbey in 1339 he was pleased to find the building in far better repair than it had been for a long time. He was most definitely not pleased to find that the most part of it was still roofless. Abbot Snow and his successor, Ralph Aske, carried on the rebuilding and it was completed around 1350.

Later Abbots left their mark on the building too. Abbot Newbury (1428 - 1473) built the central tower and transepts. Abbot William Hunt (1473 - 1481), using a great deal of his own money, carried on the work of the transepts and cloisters. Abbot John de Newland (Nailheart) (1481 - 1515) carried out extensive work and his mark or 'rebus', a heart pierced with three nails, can be seen in various places around the Cathedral. Nailheart was one of the best abbots the abbey had till then and he was also known as "The Good Abbot". Abbot Robert Elliot (1515 - 1526) built the upper portion of the gatehouse.

Bristol Cathedral from Canon's Marsh

Although not the grandest Cathedral in the country it is well worth visiting. The choir seats (Misericords) have excellant carvings on them, showing the story of Reynard the Fox, his adventures and eventual hanging. Others show more homely scenes.

After Abbot Elliot, Abbot John Somerset (1526 - 33) did make some alterations but the buildings fell into decay again and in 1533 Archbishop Cranmer stayed there for 19 days, putting right many things that were amiss. The Abbey had fallen to such a state that the Canon's had to send in the town for their meals which were given as loans or gifts. Abbot William Burton (1533 - 7) also made some slight alterations.

At the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the reign of Henry VIII it was surrendered to the Crown on 9th December 1539 by Abbot William Morgan. Henry VIII had promised that new dioceses would be founded to make up for the loss of the monasteries, but in the end only six were formed, Bristol being one of them. So, in 1542 the Monastery Church of St. Augustine's Abbey became Bristol Cathedral with Paul Bush (1542 - 54) the first Bishop.

By then the Norman nave was so decayed that it was walled off by Paul Bush, who was the first Bishop. He lies buried within it's walls. The rot didn't stop there and in the reign of Elizabeth I (1558 - 1603) the nave was let out for private dwellings and houses were built around what was left of the Abbey buildings.

The Cathedral suffered relatively lightly during the Civil War (1642 - 1651), with just the lead being stripped off the roof. The people of Bristol did far worse damage during the riots of 1831. The Bishops' Palace was destroyed and the Chapter house which contained many priceless documents was broken into. The documents were hrown to the floor and burnt. The main Cathedral building was also broken into but the Sub Sacrist or verger, a brave man named William Phillips, with an iron bar in his hands persuaded the mob to desist in the destruction of their heritage.

A great deal of restoration work was carried out between 1660 and 1685, Edward Colston (1636 - 1721) paying for a large part of it. In 1720 it was said to be in

excellent condition, but it wasn't until 1835 that the houses built on the site were demolished.

In 1836 it was decided to merge Bristol with the Gloucester diocese and for 61 years Bristol was without a Bishop. To the hurt of many Bristolians the city was known as a place with 'Half a church, half a Bishop'. They could hardly answer back as the nave was now wrecked and the place was unfit to be called a Cathedral.

Major restoration was undertaken between 1852 and 1860 and in 1868 a fund was opened to rebuild the nave. This was dedicated in 1877 and two new towers built by 1888. The architect was G. E. Street who supervised the work until his death in 1881, the work then being handed to John Loughborough Pearson. In 1897 Bristol once again became a Cathedral city.

Many eminent people are remembered in the building, the Elizabethan writer, Hakluyt (1553 - 1616), William Wycestre (15th Century writer), Edward Colston (philanthropist), Samuel Wesley (son of Charles Wesley, the hymn writer), Southey (poet), Muller (artist) and Mary Carpenter known for her philanthropic work amongst young

girls.

Saint Mary Redcliffe

Saint Mary Redcliffe

This is a wonderful church in the district of Redcliffe near Bedminster. I may be biased as I was christened here, but it really is a beautiful church.

There was a church on this spot as early as the reign of Henry I (1100 - 1135), we know this as in 1115 he gave it to Salisbury Cathedral. In 1190 Lord Robert of Berkeley gave it a water supply, a very valuable gift in the 12th Century. The water was piped from the Rugewell in Knowle.

A little later the church fell into disrepair, it was pulled down and rebuilt between 1327 and 1380 as the great church that stands today. The work was done by William Canynges whose grandson, also named William, was born in 1399.

This, younger, William continued the work on the church, and was to become the richest merchant in Bristol. In 1460 he owned nine ships, the largest being of 900 tons, and employed 800 seamen and a hundred others.

In 1446 there was a great storm and the spire collapsed onto the nave. The damage was repaired with no expense spared and with great attention to detail. There are around 1,200 roof bosses all of which are different and each one a work of art in its own right.

Restoration was work was carried out in 1927 and 1933, which was done with as much skill and attention to detail as the original work.

I have more pictures and information on St Mary Redcliffe.

This page created January 31, 2000, last modified June 22, 2022