Peter de la Mare

de la Mare was constable of Bristol Castle. In 1280 he also became Mint Keeper when the mint was opened in the castle on 2nd January 1280. In 1282 he became the jailer of Owain and Llywelyn, sons of Dafydd ap Gruffudd. de la Mare could be heavy handed as on 12th September 1279, the Bishop of Worcester accused him of breaking sanctuary by dragging William de Lay out of the churchyard of St. Philip and Jacob after he had fled there. de Lay was then imprisoned in the castle and finally beheaded. For this transgression, de la Mare and his men were sentenced to walk to that church from the Minor Friars' church in Lewin's Mead for four weekly market days dressed in their breeches and shirts and to be flogged all the way. de la Mare was further ordered to build a stone cross with 100 poor being fed at it on a certain day each year. He was

also ordered to pay a priest to celebrate mass every day for the rest of his life. The cross was mentioned by William Wyrcester in 1480, it stood on the south side of Old Market, near the corner of what was then Tower Hill. It can be seen on J. F. Nicholls and John Taylor's map of 1881 and even on the 1902 Ordnance Survey map standing at the junction of Old Market, Castle Street, Lower Castle Street and Tower Hill.

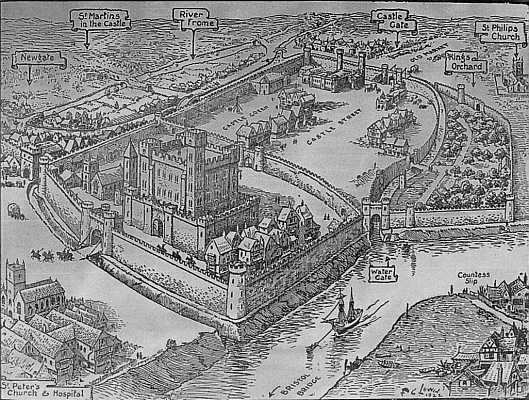

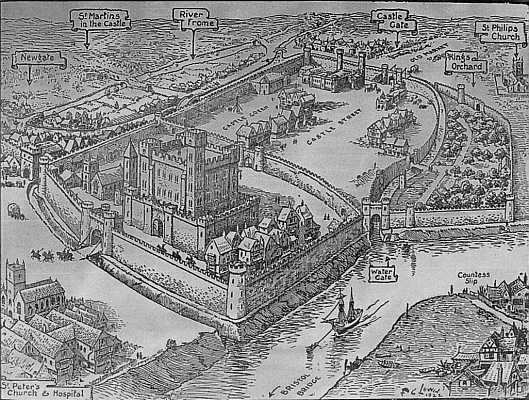

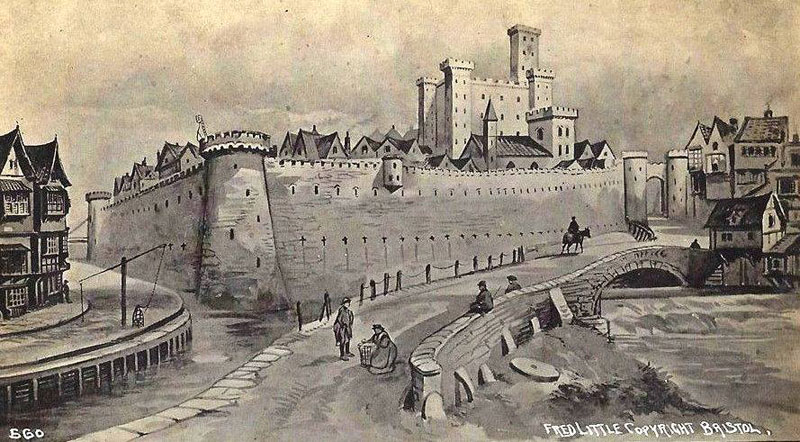

Bristol Castle in the 14th Centruy

A postcard illustrated by Fred Little

Edward II

In 1307, Edward's son, another Edward, became Edward II. He was a lot less able than his father and his lavish lifestyle made great demands on the economy.

In 1308, Edward II married Isabella of France. It wasn't going to be a happy marriage. For a start he was homosexual and spent his wedding night with a favourite, Piers Gaveston. Secondly, Isabella was to eventually cost Edward II his life - and a very unpleasant end it was too; having a red-hot poker forced into his anus. That's the popular story, but there is a lot of mystery surrounding his death - and perhaps he wasn't murdered at all. Piers Gaveston is an interesting character in British history and was beheaded in 1311.

In 1306, Sir John de Creke was appointed an assessor and collector in the county of Cambridge and in the same year received the honour of knighthood. For the first six years of the reign of Edward II he also served as Sheriff for the counties of Cambridge and Huntingdon and in 1310 he was also made one of the justices of over and terminer, for the trial of offenders indited before the conservators of peace. The following year he was given the lands and tenants of Walter de Langton, Bishop of Lichfield, who had fallen out of favour, and in 1313, together with Lord Badlesmere, Bartholomew de Badlesmere, Constable of Bristol Castle, they were mandated to, "Take charge of the town of Bristol, and hold it in safe keeping." (St. Mary the Less, Cambridgeshire)

In 1307 Lord Badlesmere had married a woman named Margaret Clare. At the time he was the Governor of the castle. (Royal Connections of the Bosley Family)

Also in 1313 Lord Badlesmere, demanded in the name of the king, a toll on all fish landed in the port. This caused civil uproar and the townsfolk refused to pay. Their leader was John Taverner. He was one of the people chosen to represent Bristol in Edward I's parliament in 1295 and had been elected Mayor twice.

A commission of enquiry was set up. Unfortunately, Lord Thomas of Berkeley presided over this. Unfortunately because he was already known to be a Royalist and so were many of the jury. While the judges were in an upstairs room of the Guildhall a meeting was held by some of the townsfolk who were encouraged to resist the enquiry. This they did by attacking the Guildhall, several of the judges broke limbs by leaping from the upstairs windows. In all, 20 men were killed in the fighting.

At this time Bristol was governed by a group of fourteen merchants, who had sided with the King, who now declared the citizens outlaws. The townsfolk drove the group of merchants out of the city and seized their goods. The King's officers were imprisoned and Taverner was appointed Mayor. A new wall was built around Wine Street to protect themselves from the castle.

Early in 1314, Edward II sent an army of 20,000 men to beseige the town with the Earl of Gloucester leading them. They were withdrawn after a short time as they were urgently needed against the Scots, who decisively defeated them at Bannockburn.

A new enquiry into the lawlessness in Bristol was set up in London in March, 1316. Not surprisingly, the people of Bristol were found guilty. The King's cousin, the Earl of Pembroke, was sent to demand their submission. He delivered a message saying that if the ringleaders were given up the rest would be pardoned. The reply from the town was...

We did not begin the strife and we have done no wrong to the king. Certain men tried to deprive us of our rights, and we defended them, as reason was we should. If, therefore, the King will take off the burdens he has laid upon us, and will grant us life and limb, chattels and tenements, then he shall be our lord and we will do his will; if not, we will go on as we have begun, and will defend our liberties and privileges even to the death.

This must have incensed the King as he now determined to end the militancy of Bristol for good. The town was beseiged again and the Lord of Berkeley blockaded the city from the sea. Siege engines installed in the castle threw boulders at the blockades in Wine Street, breaking them down. The town was forced to submit to the King. This bought fines of 4,000 marks to the town as well as arrears of all the duties due to the king. The ringleaders were imprisoned and John Taverner and his son were banished. Strangely enough the rights of the town were restored to it.

1322 saw Edward II have complete victory over his enemies and two of them, Henry Wylington and Henry de Montford, fled to Bristol. Here they were captured and hanged. The bodies of these two men were left on the gibbets until they rotted. Edward made one of his friends, was was probably as intimate with the king as Piers Gaveston had been, Hugh Despenser the Younger, Constable of the castle as well as giving him the isle of Lundy.

In 1324, war broke out with France, and Isabella and their child Edward, were sent to France to negotiate peace with her brother, the King of France. Instead, she met up with Roger Mortimer, one of Edward's expelled Barons, and they began an open affair. Isabella and Roger managed to raise an army and invaded England in 1326.

The Despensers

Bristol declared itself for her but Edward took refuge here and put the elder Despenser, who was 64, in charge of the castle. Isabella took Gloucester castle then marched south to Bristol. Edward and the younger Despenser escaped by boat, but the elder Despenser was captured. He was hung on 27th October 1326, just outside of the town in his armour, cut to pieces and the bits given to the dogs. His head was sent to Winchester. The younger Despenser met a similar fate at Hereford in November 1326, his head ended up in London.

John Smyth of Nibley writing in 1361 described both executions...

Alonge with the Queene and prince and their Army goeth this lord Thomas to Bristoll, where Hugh Spenser the elder Earle of Winchester was taken, And without answering for himself was drawn and hanged in his Armor, taken down alive, and bowelled, his bowells burnt, his head smote of and sent to Winchester, his body hanged up againe and after fower dayes cut to peeces and cast to dogs to bee eaten.

Thence through Wales in search after the kinge, the Queene and her Army come to Hereford; The kinge on the 16th of November is found out and taken, with Hugh Spenser the sonne Earle of Gloucester; The kinge is conveyed to Kenellworth, The Earle is brought to Hereford, where clad in his coat Armor he was dragged to the place of execution, where beinge first hanged upon a gallows fifty foot high, was afterwards beheaded and cut into quarters, his head sett up at London, and his quarters in fower parts of the kingdome. (Hugh Le Despenser: Three Generations) (Internet Archive)

This family must have liked losing their heads. A descendant of theirs, Thomas, was born 1373, an MP in 1396, created Earl Gloucester on 29th September 1397, beheaded at Bristol in January 1400.

Death of Edward II

The day the castle surrendered to Isabella in 1327, her son, another Edward, was declared King. Edward II was soon captured and returned to Bristol where he was made to wear a crown of hay and taunted by the soldiers. From here he was taken to Berkeley, where he led a miserable existence. He was thrown into a waste pit and forced to eat rotten food and drink foul water. Dead animals were even thrown into the pit, but he still did not die.

Practically everyone wanted Edward II dead, but no-one wanted to be accused of it. A plan was devised. On the night of 21st September 1327, a knight named Gurney joined Lord Maltravers as gaoler. They inserted a straight cow horn with the point removed into Edward's anus, then a red hot iron was pushed through the cow horn and into the body, burning out his entrails. This killed him while leaving no marks on his body, making it appear as if he had died of natural causes. The crime might have gone unnoticed if they had not murdered him in an outbuilding: as it was, his screams could be heard all over the village. When the crime was investigated, Thomas Berkeley produced an alibi that he was ill and staying five miles away at Wotton Under Edge. He was acquitted. In the 1600s, a historian found papers revealing that Thomas Berkeley did not attend Bradley Court, Wotton Under Edge until a week after Edward's murder. No one was ever found guilty, mainly due to Thomas Berkeley concealing Gurney and exiling him to Beverston.

That's the popular story, but there is a lot of mystery surrounding his death - and perhaps he wasn't murdered at all.

William Scrope

William Scrope or more properly Sir Williem Le Scrope, K.G., King of Man met his end at Bristol Castle in 1399. Born into the illustrious Scrope family around 1351 he served his country well, right up until he had his head chopped off. He was the eldest son of Sir Richard le Scrope, of Bolton, Lord Chancellor, afterwards created Lord Scrope of Bolton. His mother was Blanche, sister of Michael de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk. As a youth he served under John of Gaunt in the Hundred Years' War, during which he was knighted for valour. Amongst many other dignities, in 1389 he was appointed Constable of the Castle of Queenborough, Governor of Beaumaris Castle, and Chamberlain of Ireland, in 1391 he was given a grant of the Castle of Bassburgh for life, and in 1394 a grant of the Castle and Town of Marlborough. In 1394 he was elected a Knight of the

Garter, and was appointed Vice-Chamberlain of the Household, and in 1396 he was appointed Lord Chamberlain.

In 1393 he purchased the Isle of Man from William Montacute, Earl of Salisbury and so became the King of Man. In 1398 Thomas, Earl of Warwick, on his banishment to the Isle-of-Man, was entrusted to the care of Sir William le Scrop and Sir Stephen his brother, to carry him safely to the said Isle and to guard his body there, their own bodies to answer for it, without letting him depart from the said Isle. Probably the fact of his being King of Man may have been the reason why this duty was entrusted to him. It is recorded that he received the sum of £1074 4s. 5d. for charges and expenses in connection with the safe conduct of the Earl of Warwick to the Isle of Man, and for his support there.

He was created Earl of Wiltes in 1397. In 1398 he was appointed Ambassador to treat for peace with Robert, King of Scotland, and later was made Lord Treasurer of England. The following year King Richard II. appointed him one of the three Guardians of the Realm during his (the King's) absence in Ireland. The Queen Isabel (then only eleven years of age) was placed under his care at Wallingford Castle. From thence he retired to Bristol Castle, where he was defeated by Henry of Bolingbroke, and beheaded without trial, in July, 1399. His head was sent in a white basket to London and placed on London Bridge. After the accession of Henry IV, it was delivered to his widow. (Sir Williem Le Scrope, K.G.)

William Scrope - Sir Williem Le Scrope, K.G., King of Man - 1389

Image from Sir Williem Le Scrope, K.G.

Bristol Castle around 1400

Image from "The Story of Old Bristol by E.M. Habgood (Industrial Art/Dolphin Publicity, 1966, 2nd Ed. Page 2)

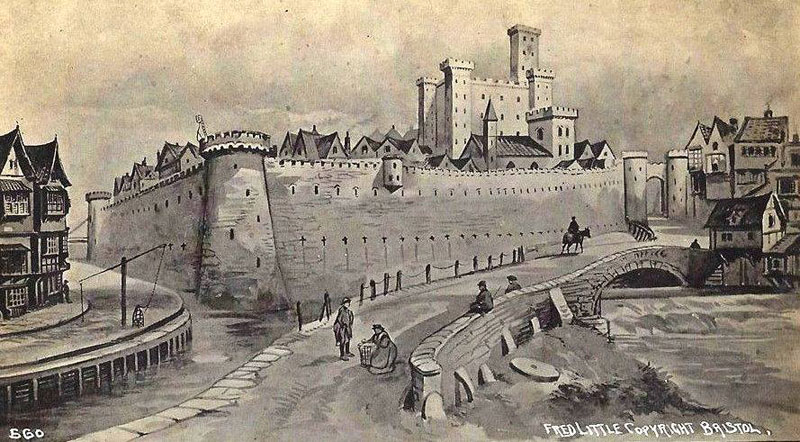

Bristol Castle from Broad Weir in the Fifteenth Century

Another depiction by Fred Little

War of the Roses

By 1402 the manor of Barton had become much depleted with only 40 acres being under the direct control of the Constable of the castle with much of the surrounding land leased out to local landowners. A surviving rent roll of 1498 shows land at Oldbury as owned by the wealthy Bristol merchant, Philip Grene, sheriff of Bristol in 1499/1500 whose daughter Joanna was married to John Kemys of Oldbury. Grene was also shown as owning two mills on the River Frome, which had been under the control of the Constable of Bristol castle during a earlier period, one of which Oldbury mills was rented from him by John Kemys.

The War of the Roses (1455 - 1485) was a power struggle between Queen Margaret, the wife of Henry VI and the Lancastrians who took for their emblem the Red Rose and Edward of York, who took the White Rose. It appears that most of the towns in England at the time were left relatively unscathed by the battles that were raged around them, but the Barons would lead their followers into many bloody battles where thousands were killed.

In common with many other places, Bristol seemed to have changed sides more than once during the conflict. In 1456, Queen Margaret arrived in Bristol and was royally entertained by the Canynges. Edward IV of York arrived here in 1461 and was similarly greeted, again, most of the cost was born by Canynges, who was now Mayor for the fourth time. Whilst here, Edward climbed the tower of St Ewen, and looking out of the east window watched two of his enemies, Sir Baldwin Fulford and John Heysant executed in the High Street. It wasn't all sightseeing though, there was work to do. Whilst he was in Bristol, Edward IV appointed Lord Stafford of Southwyk Captain of Bristol Castle, a promotion above his appointment as Constable. This led to a few grumblings as it was in opposition to a charter granting the Mayor disposition of the castle.

Ten years later, Margaret again arrived in Bristol where she was given supplies and received reinforcements when some of her local supporters joined her army. Her plan was to link up with another army in Wales that had been raised by her husbands family. At that time the River Severn was impossible to bridge, and so she made her way north to cross where it was narrower. When she arrived at Gloucester she found that Edward had ordered that town to be shut against her and she was heavily defeated a little further north at Tewksbury. Edward didn't forget the aid Bristol had given her and heavy fines were levied against the town.

Bristol Castle ~ c1500

Wyrcester's Account of the Castle

On 26th September 1480, William Wyrcestre (or William of Worcester) arrived in Bristol and gave an account of the castle. His "Notes on Bristol" was written partly in English and partly in Latin. In his 1824 book, "A Chronological Outline of the History of Bristol", John Evans gives a translation of Wyrcestre's notes...

The road from the gate of the entrance to the Castle of Bristol [meaning the gate of the deep ditch across the bridge to the doors of time entrance] is near the E. part of the church of St. Peter; and you go on marching by the wall of the ditch of the walls of the Castle, through New Gate and along the street called the Weer, and over Weer-bridge, leaving the watering-place on the left hand, and making a circuit by the wall of the Castle-ditch towards the south, near the Cross in the Old Market; thus continuing to a great stone about a yard high, of freestone, erected at the extremity of the bounds of the city of Bristol; so proceeding on to the gate of the first or eastern entrance of the Castle, at the west part of St. Philip's Church, which is at the end of a lane behind the Old Market. This contains, in a circuit of one

part of the tower and walls of the Castle, four hundred and twenty steps.

The whole circuit contains two thou?sand one hundred steps. [His steps vary, but are about twenty-one inches.]

The quantite of the Dongeon of the Castell of Bristol, after the inforinatione of ... porter of the Castell. The tour called the Dongeon ys in tiiykness, at fote, 25 pedes, and at the ledying-place, under the leede cuvering, 9 feet and dimid; and yn length, este and west, 60 pedes, and, north and south, 45 pedes; with fowre toures standyng uppon the fowre corners; and the hyghest toure, called the mayn, i. e. myghtyest toure above all the fowre toures, ys 5 fethym hygh abofe all the fowre toures; and the wahlys be in thykness there 6 fote. Item, the length of the Castelle, wythynne the wallys, este and weste, ys 180 virgae. Item, the brede of the Castelle, from the north to the south, wyth the grete Gardyn, that is, from the Watergate to the mayng rounde of the Castelle, to the wall north?ward, toward the Blak Frerys, 100 yerdes. Item, a bastyle, lyeth southward beyond the Watergate, conteynyth yn length, 60 virgae. Item, time length from the buliwork at the utter gate, by Seynt Phelippes chyrch-yerd, conteyneth 60 yerdes large. Item, the yerdys called sparres of the Halle Royalle conteynyth in length about 45 fete of hole peee. Item, the brede of every sparre at fore conteynyth 12 onch ajul 8 onches.?

The Porch or entrance into the Hall is ten yards long, with an arched vault over, at the entrance of the Great Hall. The inner entry into the porch of the Hall is 140 steps, - meaning the space and length betwixt the gate of the Castle-walls, and the walls of the area of the utter-ward. The length of the Hall is 36 yards, or 52 or 54 steps; the breadth of the Hall is 18 yards, or 26 steps. The height of the walls outside the Hall is 14 feet, as I measured them. The Hall, formerly very magnificent in length, breadth, and height, is all tending to ruin. The windows in the Hall double, the height (de 11 days) contains 14 feet. The length of the rafters of the Hall is 32 feet. The Prince's Chamber, on the left side of the King's Hall, is 17 yards, in breadth 9 yards, and has two pillars made with great beams, but very old. The length of the front before the Hall with ... is 18 yards. The length of the marble stone table is 15 feet, situated in another part of the Hall, for the King's table there sitting. The length of the Tower in the east part of it, is 36 yards; its breadth at the western and south part is 30 yards. The length of the utter ward of the Castle, from the middle gate, and lately separated from the inner ward of the Chapel, the principal chamber of the Hall, is 160 steps. The length of the first entrance to the Castle, by the gate, is 40 steps; that is, from the street of the Castle, by entering at the first gate of the Castle into the utter ward, The Chapel in the utter ward, or first ward, is dedicated in honour of St. Martin; but, in devotion to St. John the Baptist, a monk of St. James ought to celebrate the office every day, but does it but Sunday, Wednesday, and Friday. - There is another very magnificent Chapel, for the King and his Lords and Ladies, situate in the principal ward, on the north side of the Hall, where beautiful chambers were built, but are now naked and uncovered, void of planchers or roofing. - The dwelling of the officers of the kitchen belong to time inner ward near the Hall, on time left side, that is, on the south part of the Hall. The dwelling of the Constable or Keeper is situated in the first or utter ward, on the south part of the magnificent tower, but is all pulled down and ruinous, which is great pity.

John Leland was appointed King's Antiquarian in 1533 and authorised by King Henry VIII to have access to tany places where records were stored, including Cathedrals, Abbeys, Priories - and castles. In 1534, he arrived in Bristol and later wrote...

In the Castle be two courtes. In the utter courtes, as in the north-west part of it, is a great dungeon-tower, made as it is said of stone browghte out of Cane in Normandy, by the redde Erle of Gloucester. A praty churche and much loggyng in the area; on the southe syde of it a great gate, a stone bridge, and three bullwarks. There be manie towres yet standynge in both courtes; but alle tendith to ruine. The Castle and most part of the Towne by northe standith upon a grownde metely eminent, betwixt the ryvers Avon and Fraw, alias Froom.

In the mid 1500's public land was being enclosed, this led to civil unrest as without common land people couldn't graze their animals, collect plants for eating or get the odd rabbit for their pots. Adam's in his "Chronicles of Bristol" says that...

This year [1549] in May was a great rising in this city; and many men broke down hedges and thrust down ditches that were enclosed near the city; and then they made an insurrection against the mayor [William Jay], who with the council and many armed men in their defence went into the Marsh, where the matter was taken up, and within 4 days after the chief rebels were taken one after another and put into ward, but none of them were executed. The walls of Bristoll and the castle were armed with men and ordnance, and most of gates made new, with watch and ward every day for fear of rebellion.

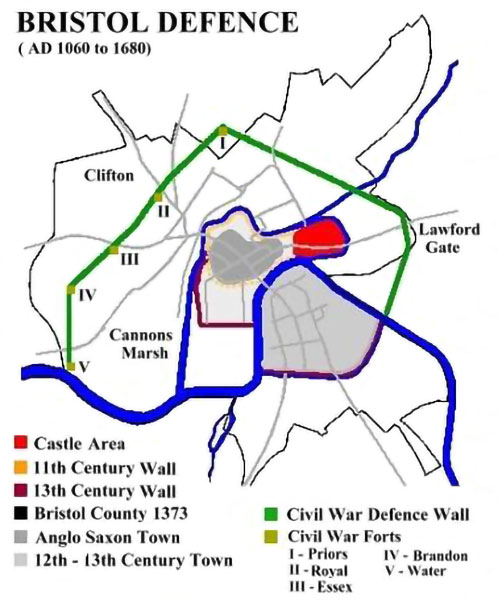

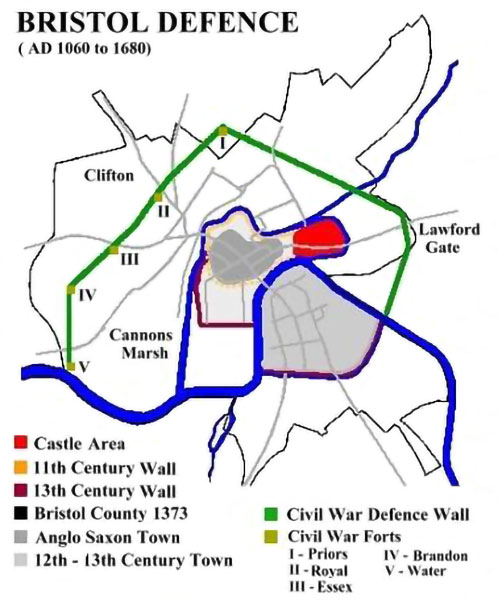

Outline of Bristol defences 1060-1680

More Taxes

From the end of the 16th Century Parliament and the Monarchy were taking separate stances. The cause of the rift between the two were those old favourites, Religion and Money.

While religious dissent was increasing so was dissatisfaction with the expenditure of the monarchy. The increasing amount of gold from the New World was decreasing the value of money at home; the value fixed rents from Crown Lands were similarly decreasing. The income from Customs and taxes was not enough to make good the loss and Parliament was unwilling to increase its contribution without wanting to have more say in policy making. This, the monarchy couldn't accept without infringing their Devine Right as kings.

James I (1603 - 1625) began to put taxes on items not agreed with Parliament. He also revived the old custom of Purveyance. In feudal times, the king travelling through the country would receive food, drink and lodging from whatever town or district he found himself. James I imposed a new tax, the "Composition of Purveyance", on merchants. Those traders who refused to comply found that their goods would be seized.

In 1604, the Mayor, Alderman Whitsun, declared that this was illegal and was issued a letter threatening him with further action by the Board of Green Cloth, a committee set up by the king to oversee such matters. Whitsun took this letter to Parliament, who complained to the king, who went into a rage.

The next year, 1605, the King's Purveyors arrived in force in Bristol and removed 51 hogsheads of claret and 10 butts of sack. They did leave promises of payment but these were well below market value for the wines. The Corporation repaid the £350 to the merchants but reclaimed it as taxes from the port.

In 1608, the king put a new tax onto sweet wines entering the Port of Bristol, even though a tax of 10% called "prissage" was already being paid on it. The new tax was later dropped due to the merchants bribing the port officials, but they were forced to pay purveyance whenever the king came within 20 miles of the city. Even this was very expensive, in 1613, when the Queen visited Bath, Bristol merchants had to provide 5,200 gallons of wine (how much did these people drink in those days!), sugar and other groceries. The bill for this was over £1,000.

As well as the resurrection of Purveyance, King James also reintroduced the Tudor custom of "Monopolies". This was a licence issued by the King to individuals or groups for the sole right to trade in a particular area or product. Anyone else wishing to share the trade would have to come to some arrangement with the Monopolist. As you can suspect this caused a great discontent amongst most traders.

Examples of these monopolies were those issued in 1620 to London companies for the sole right to make clay pipes and another to make starch. Both were also made by merchants in Bristol who were forced to abandon their trades.

Charles I also used the Monopoly system to raise money and in 1631 gave the right to make soap to another London company. This licence was far reaching in that the Monopolist also had thee right to destroy the buildings of any others who carried on the trade of soap manufacture. Soap making was long established in Bristol and several merchants faced ruin. They came to an agreement with the London company to let them make 600 tons of soap a year. The king claimed a special tax of £4 per ton on these 600 tons. There were often disagreements over the amount made and around 30 Bristol soap makers were instructed to make their way to London. At the time this was a very expensive and time-consuming journey. Once there, the merchants were fined a total of £20,000.

There were winners as well as losers in Bristol under the monopolies system. In 1618, a monopoly was given to a London merchant for the export from South Wales of butter. The licence was to last for 21 years and the monopolist would have to pay the Crown one shilling (a 20th of a pound) for every kilderkin (18 gallons) of butter. For a two thirds share in this trade Bristol merchants paid £400 cash, an annual rent to the Crown and 2 shillings per kilderkin to the monopolist. Even after this outlay they still made a profit. The Welsh butter exporters were put out of business.

Other local traders secured the right to export 120,000 calf skins per annum for 40 years. This was very profitable.

The examples given above explain why on the outbreak of war most of the wealthy traders were for the Royalist's and most of the smaller ones were in favour of the Parliamentarians.

In 1602, Sir John Stafford was made constable of Bristol Castle, but in March the same year the Mayor petitioned the king that Sir John wasn't resident and was content to leave his office to a mean and untrustworthy deputy. The deputy had allowed 49 families, consisting of around 240 people, to live in the castle and who who seemed to exist by begging and stealing.

Francis Brewster managed to obtain the lease of the castle for eighty years at a rate of £100 per annum on 23rd August 1626.

By 1629, the castle was becoming ruinous, it had been neglected for over a hundred years. The post of Constable had become a sinecure and because civic officials were not allowed within the castle precincts they had become a refuge for thieves, malefactors, vagabonds and able-bodied men capable but unwilling to be conscripted for war service. On 13th April 1629, at a cost to the city of £250, granted that the castle should be forever parted from Gloucestershire and be made part of the City and County of Bristol. Mining and other rights were not included with the agreement with the king and Bristol had to continue paying a rate of £40 per annum for these.

What Bristol really wanted was full control of the castle and they petitioned the king for such. On 26th October 1630, for a payment of £959 and further fees of £250 they got it. The king granted the City of Bristol the entire royal estate in the city, this included the castle, mansion house, various dwellings, the King's Orchard and the Lower Green. In 1631 a new armour house was built in the castle.

Francis Brewster was still the sitting tenant and in September 1634, the city bought the lease from him for £520.

Another Royal scheme for raising money was the introduction of Ship Money. This at first sight was very laudable, as it made the whole country take a share in the upkeep of the Navy, and hence the defence of Britain. After a while though it became apparent that it was another scheme to fill the Royal coffers.

In October 1634, Bristol's contribution to the Ship Money was £2,166 13s 4d. In 1635, another £1,200 was demanded. In 1636 and 1637 another £800 was demanded. Resistance was growing and the money for 1637 was only collected with difficulty. In 1638 the sum due was only £250. In 1639 it was raised again to £640. Some people refused to pay and their goods were ordered to be sold, but no one offered to buy them. In 1640 the Long Parliament scrapped Ship Money altogether.

In 1642, the five members of Parliament who were loudest in their opposition to the Ship Money were arrested. One of these was Mr. Pym, a Somerset Member of Parliament, whose arrest no doubt polarised feelings around Bristol.

This page created April 8, 2005; last modified November 6, 2022