Bristol, in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries suffered from some of the worst riots in the country's history. There is an odd thing about the aftermath of all these riots, and this is the lack of severe reprisals against, or punishment of, the rioters. It is true that many, many people died or were severely injured at the time but relatively few were ever bought to trial and fewer still executed or imprisoned. It may have been the authorities didn't want more trouble than they already had or that they had a genuine sympathy for the peoples' grievances. There was also the matter of finding witnesses and juries for the trials. Perhaps the witnesses and juries had their own sympathies with the rioters or it could have been that they feared some sort of reprisal. Although the poorer Bristolians appeared to do most of the rioting, there are numerous reports of more prosperous citizens on the edges of these riots, not actively taking part but certainly obstructing the city constables and troops from acting as efficiently, or maybe as brutally, as they otherwise would.

Tax Riots: 1312 - 1316

This was the earliest recorded riot in Bristol. The king, Edward II, was not one of Britain's best rulers and already unpopular when he introduced another tax on shipping. The Mayor, William Randolph, took over control of collecting the taxes and the ship money from Bristol. Rioting started soon after and Edward II appointed the Constable of the Castle with powers to overrule the city council. Although he was given the income from the city as his own he never dared enter the city and Lord Thomas de Berkeley was appointed to put down the rioters. Twenty men were killed and the King's officers had to take refuge in the castle. They remained under siege until 1316 when the army was called back to Bristol.

In 1313, Lord Badlesmere, demanded in the name of the king, a toll on all fish landed in the port. This caused civil uproar and the townsfolk refused to pay. Their leader was John Taverner. He was one of the people chosen to represent Bristol in Edward I's parliament in 1295 and had been elected Mayor twice.

A commission of enquiry was set up. Unfortunately, Lord Thomas of Berkeley presided over this. Unfortunately because he was already known to be a Royalist and so were many of the jury. While the judges were in an upstairs room of the Guildhall a meeting was held by some of the townsfolk who were encouraged to resist the enquiry. This they did by attacking the Guildhall, several of the judges broke limbs by leaping from the upstairs windows. In all, 20 men were killed in the fighting.

At this time Bristol was governed by a group of fourteen merchants, who had sided with the King, and who now declared the citizens outlaws. The townsfolk drove the group of merchants out of the city and seized their goods. The King's officers were imprisoned and Taverner was appointed Mayor. A new wall was built around Wine Street to protect themselves from the castle.

Early in 1314, Edward II sent an army of 20,000 men to besiege the town with the Earl of Gloucester leading them. They were withdrawn after a short time as they were urgently needed against the Scots, who decisively defeated them at Bannockburn.

A new enquiry into the lawlessness in Bristol was set up in London in March, 1316. Not surprisingly, the people of Bristol were found guilty. The King's cousin, the Earl of Pembroke, was sent to demand their submission. He delivered a message saying that if the ringleaders were given up the rest would be pardoned. The reply from the town was...

"We did not begin the strife and we have done no wrong to the king. Certain men tried to deprive us of our rights, and we defended them, as reason was we should. If, therefore, the King will take off the burdens he has laid upon us, and will grant us life and limb, chattels and tenements, then he shall be our lord and we will do his will; if not, we will go on as we have begun, and will defend our liberties and privileges even to the death."

This must have incensed the King as he now determined to end the militancy of Bristol for good. The town was besieged again and the Lord Thomas of Berkeley blockaded the city from the sea. Siege engines installed in the castle threw boulders at the blockades in Wine Street, breaking them down. The town was forced to submit to the King. This bought fines of 4,000 marks to the town as well as arrears of all the duties due to the king. The ringleaders were imprisoned and John Taverner and his son were banished. Strangely enough the rights of the town were restored to it.

Apprentices Revolt: 1659

In 1659 the Bristol apprentices revolted, demanding a free Parliament and the restoration of the monarchy. The rioting was only stopped after great difficulty. By 1660 most of the people of England were tired of the Puritan ways and having King Charles back on the throne was the signal for many celebrations. On 5th March 1660, the bellman of Bristol made the usual Puritan proclamation banning cock-throwing and dog tossing. The rowdy apprentices attacked him and the next day, which was Shrove Tuesday, squailed a goose and tossed cats and dogs into the air outside the Mayors Mansion House. To squail a goose was to throw sticks, weighted with lead at one end, at it. The object was to maim the bird as much as possible without killing it. This time the disorder of the apprentices was soon quelled and the authorities set about their own celebrations.

Food Riot: 1709

In 1709 the price of food rose alarmingly. A bushel of wheat doubled in price from 4 shillings to 8 shillings. Two hundred coal miners from Kingswood, always a rowdy bunch, marched into the city and, joined by some of the citizens, raised a riot. They were promised a reduction in the price to 5/6 (5 shillings and sixpence) a bushel and soon dispersed.

Political Riot: 1714

On 20th October 1714, a celebration for George I, who just had become king, turned into a riot. Two people were killed, one was trying to stop the riot and the other was a rioter killed by a man defending his house. It was decided that a "show trial" was needed to prevent the unrest from spreading outside of the West Country. The procession of judges entering the city caused further civil disorder. The crowd were shouting "No Jeffreys, no Western Assize" showing that the events following the Monmouth Rebellion in 1685 were still fresh in their minds. It was suspected that the Tories and their "Loyal Society" organized the attacks on the Whigs and Dissenters. This was never proved and from the 500 rioters only six were put on trial. The Tories certainly did try to influence the trial by bribing witnesses, but not many could be found to speak against the rioters. The six people on trial escaped with relatively light sentences, three months in prison and a fine each.

Weavers Riots: 1728 / 1729

Although on the whole a wealthy city, groups of Bristolians suffered as much as others the difficulties that any traders and manufacturers have to endure. Added to these difficulties was the fact that Britain was often at war with her European neighbours. Bristol weavers, who were largely based outside of Lawfords Gate, found themselves in financial difficulties starting in 1727. They rioted several times during 1728 and 1729, wrecking looms and attacking unpopular employers. On 29th September 1729 the mob marched to Castle Ditch and the house of Stephen Freacham. Freachham fired into the crowd, killing seven people. Soldiers were sent to disperse the mob and Freacham accidentally shot one of them. Freacham was arrested for the murder of the soldier and escaped hanging by applying to the Government for a pardon. Unfortunately I wasn't able to find any further information about this as I would have like to know if he was ever tried for the killing of the rioters.

Turnpike Riots: 1727 - 1749

The introduction of tollgates on 26th June 1727 sparked off far more serious riots than those of 1709 or 1714. Two days later the turnpikes had been destroyed and the Mayor of Bristol was warning the Duke of Newcastle that trouble was in store for the city. Wherever they appeared the tollgates were wrecked. For a time, in 1734, not a single tollgate was left standing between Bristol and Gloucester. This continued for 21 years, the length of time the Act of Parliament that allowed the tollgates was in force. The turnpike trustees wanted a new Act and the turnpikes were wrecked twice again in July 1749. Three of the rioters were arrested and put into Newgate prison. On 28th July 1749 the Turnpike Trustees warned of impending trouble. Three days later, on 1st August 1749 it arrived. Several hundred farm labourers destroyed some of the turnpikes and demolished the house of one of the officers that had arrested the rioters the previous month. Finding the city gates shut against them they destroyed more turnpikes. One of the Turnpike Trustees led some citizens and around fifty sailors armed with cutlasses against the rioters and caught 28 of them.

The Duke of Newcastle was again warned of further trouble and in response he sent a regiment of Dragoons against the rioters. Against this force the rioters could do nothing and peace was restored on 5th August. Two of the people responsible for demolishing the officers house on 1st August were hanged. Because of local sympathy other rioters were sent to Wiltshire for trial, but not one was convicted. Five of them, however, died of smallpox in prison awaiting trial. The hangings and the fear of armed response obviously had the desired affect as there were no more trouble concerning the turnpikes after 1749.

Food Riot: 1753

Very bad harvests in 1752 was the cause of fresh rioting four years later in 1753. This time four people were killed and over fifty were injured. After the failed harvest a disease swept through the cattle herds forcing the price of meat up, though the main cause was again the high price of bread. On 21st May 1753 rioters marched from Kingswood to Bristol. Once again the miners of Kingswood were cited as the main trouble-makers. Most of the crowd dispersed on promises from the council to reduce prices as soon as possible. A major grievance of the crowd was that grain was still being exported through the city while domestic prices were kept high. There was some truth in this as the rioters broke into a ship, "The Lamb", that was preparing to sail with 70 tons of wheat to Dublin. The mob returned to the Council House and smashed most of the windows, but at least one of the rioters was captured. The mob threatened further trouble to release the prisoner.

On 25th May 1753, a mob of 900, made up mostly of colliers and weavers, broke into the Bridewell and released the prisoner. Fighting broke out between the rioters on one side and the constables of the city and a troop of the Scots Greys calvary, who had arrived from Gloucester that morning, on the other. Four rioters were killed, around fifty injured and thirty were captured. The rioters managed to capture five people, the city forces were able to rescue three but the other two were taken to the coalpits.

A couple of days later the two people captured by the rioters were released, the city authorities sent doctors to care for the wounded and a collection was organized for the poorer of the miners. One of the three people captured by the rioters and rescued was John Brickdale. Brickdale was probably targeted by the rioters as he was the man who led charge of citizens and sailors against the Turnpike Rioters in 1749. His troubles were not over with his rescue as he was arrested for the murder of one of the rioters, William Fudge. As in the case of Stephen Freacham in the Weavers Riots of 1729 the Government quashed the charges before he could be tried.

Bristol Bridge Riot: 1793

This is the bridge that gave Bristol or Brygstowe, the place of the bridge, as it was originally known its name. The original bridge was built at the place where one could be most easily built across the River Frome. The original Saxon (approx. 600 A.D. - 1066) bridge would have been built of wood. A new bridge was built in 1247. This was still made of wood but had houses down both sides. These were five stories high that overhung the river.

By 1755 it was obvious that Bristol Bridge was no longer fit for service, it had, after all, been built in 1247, and was now over 500 years old. In 1760 a bill to replace the bridge was carried through parliament by the Bristol MP Sir Jarrit Smyth. The new bridge was built by Thomas Paty who headed a company of commissioners between 1763 and 1768. The commissioners were allowed to collect tolls for its building and upkeep on it. After 26 years of toll collecting the company had over £3,000 in hand and people were clamoring for the tolls to cease. It was promised that the tolls would be scrapped on 29th September 1793, but a few days before this bills were printed saying that the tolls were available for sub-letting. The financing of the Bridge was more complicated than this though. The city taxes on its citizens were raised as were the port taxes. At this time it must be remembered that the City Council was not an elected body but a sort of "Gentlemans' Club" made up of the rich and famous. This also caused trouble in 1803 over the rebuilding of the city docks. Some members of the Council were also Commissioners for the bridge.

The financing wasn't the only problem the new bridge faced. There were heated debates about it's structure and form. Were the old foundations still stable enough? How many arches should it have? These arguments dragged on for years. In September 1761 a temporary footbridge was built but carriages and carts were soon using it. James Bridges had submitted plans for the new bridge in 1758 and after all the wrangling and arguments it was this plan that was finally adopted. The three arched bridge was built on the foundations of the old bridge first laid in 1245. The new bridge was opened in November 1768 and had cost £49,000.

In 1786, the Act that controlled the taxes and tolls expired. This Act, like the Turnpike Acts, were only in force for 21 years at a time. The Commissioners for the bridge reapplied for a new Act, this time with provision for demolishing houses on the approaches to the bridge. A corn and butter merchant, David Lewis, of Bridge Street, opposed the new Act and built up a sizable following. Following the introduction of the new Act it was David Lewis that purchased the first lease to collect the tolls on the bridge, and although he received recognition for forcing the leasing of the tolls from the Commissioners it was his tollgates that were destroyed in 1793.

It was a hanging offence to destroy even the boards on which the tolls were publicized, but on 19th September 1793 a mob gathered and destroyed the tollgates. The Herefordshire militiamen were ordered to fire a warning shot over the heads of the rioters but a 60 year old plasterer, John Abbot, who was on his way home, was killed.

The inquest of this unfortunate man shows very clearly the feelings of both sides. The Mayor initially refused an inquest, then relented but directed the coroner to return a verdict of justifiable homicide. The jury had other ideas and pronounced a verdict of willful murder by the person or persons who ordered the militia to fire. The coroner eventually returned a verdict of murder by persons unknown.

By Saturday, 28th September the tollgates were back, as were the crowd, who destroyed the new ones. The constables and troops who were sent to disperse them were pelted with stones. The next day, Sunday, the barriers on the bridge were re-erected and the Commissioners tried to collect tolls on people using the bridge. The Riot Act was read three times and in the evening the crowd dispersed.

On Monday 30th September a mob arrived in force and had the Riot Act read to them three more times. The crowd ignored this and started pelting the soldiers. The Mayor had already ordered the soldiers to fire upon the crowd if resistance was met, this they did, without any warning. Ten more people were killed, and at least another fifty wounded. Many of those hit were reported as not being part of the mob but innocent bystanders, in fact one of those killed was a man visiting Bristol on business. The reward for the soldiers was that their commander, Lord Bateman, was given 100 guineas.

There were calls for charges of murder to be brought against the Council and members of the Commissioners as well as the publishing of the accounts for the new bridge. The Council for their part insinuated that a few radicals were behind the riots rather than believe that they and the Commissioners had mishandled the situation, both in terms of the finances of the bridge and what happened in those few days in September. All of those witnesses to the riots that could be found claimed that they were there as bystanders rather than face the consequences of admitting that they took part, which is hardly surprising given that they could, if the law was exercised to its fullest extent, be executed.

Market Riot: 1811

As in the food riot of 1709 the cause was the rising price of food. This time the cause was butter which was increased in price to 2s 6d a pound.

Political Reform Riot: 1831

The worst riots that Bristol, and probably the entire country, experienced was the reform riots of 1831. In November 1830, the Prime Minister, Earl Grey, informed King William IV that parliamentary reform was needed. Bristol had been represented in the House of Commons since 1295, but by 1831 little more than 6,000 people of the population of 104,000 had the right to vote. The fast growing industrial towns such as Manchester, Birmingham, Bradford and Leeds had no representation at all, whilst some once thriving centres of population had dwindled to villages, a couple of houses or had disappeared altogether but were still allowed to return Members to the House of Commons. This last group of constituencies were known as Rotten Boroughs, and for good reason. Most of these constituencies were under the control of one man, the patron, who in many cases was the landlord. Rotten boroughs had very few voters. For example, Dunwich in Suffolk, as a result of coastal erosion, had almost fallen into the sea and by 1831 only had thirty-two people allegeable to vote. Old Sarum, in Wiltshire, only had three houses and a population of fifteen people. With just a few individuals with the vote and no secret ballot, it was easy for candidates to buy their way to victory.

The Reform Bill was to be introduced to address all of these problems. It was to give more people the vote, ensure the new towns were properly represented, re-draw the boundaries of the voting areas and stop people buying their way to office.

Early in 1831, Lord John Russell had his Reform Bill defeated in Parliament. Lord Grey's attempt on 22nd September passed through the Commons but was rejected by the Lords. In the Commons, one of the most outspoken opponents to the Bill was the Recorder of Bristol, Sir Charles Wetherall.

On 24th October there was civil disorder when the Bishop of Bath and Wells arrived in Bedminster to consecrate the New Church.

Sir Charles Wetherall arrived in Bristol on Saturday, 29th October to open the Assize Courts, his carriage was pelted with stones all along his route through the city. The Court was opened but violent interruptions caused it soon to be adjourned. Sir Charles was driven to the Mansion House in Queen Square, pelted and jeered at all the way.

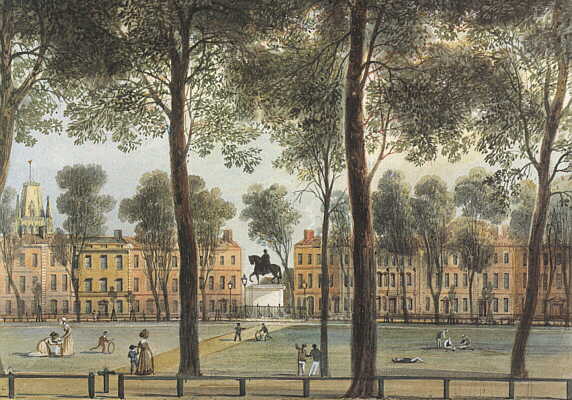

Queen Square in 1827

This watercolour by T. L. S. Rowbotham (1783 - 1853)

This painting is in the collection of Bristol Museums and Art Gallery

To the left can be seen the old turret of St Mary Redcliffe.

In 1702 Queen Square was laid out in its present form, and new houses were built there in 1753.

Mansion House Queen Square - 1824

A watercolour by Samuel Jackson

Image from "Civic Treasures of Bristol" by Mary E. Williams (City of Bristol, 1984, ISBN 0900199245)

There wasn't a city owned Mansion House where the mayor could entertain guests until this house was acquired for the purpose in 1786.

Being the property of the city for only 45 years, it was totally destroyed by the riots of 1831.

It was feared that Sir Charles' life was in danger and so two troops of the 14th Light Dragoons and a troop of 3rd Dragoon Guards under command of Lieutenant Colonel Brereton was called for. The 14th Light Dragoons had been used to quell riots here before, were nicknamed the Bloody Blues and hated. In all these Dragoons were composed of 93 soldiers. In the city there were also around 100 constables and another 119 men were used as "specials", though these were later described as "bludgeon men". These forces were never used effectively together, one constable was warned by a soldier that if he didn't stop attacking the rioters with his sword the soldier would cut the constable down with his.

On his arrival Brereton found all the windows of the Mansion House smashed and rioters tearing up the railings and paving stones around the Square. The Riot Act was read but Brereton would not fire into the crowd unless the Mayor gave him direct orders to do so. The Mayor, Charles Pinney, declined to give such drastic orders and Sir Charles Wetherall had to make his escape over the rooftops.

Rioting ceased around dusk and the soldiers drew their swords and charged across the Square. The Square was soon cleared but it left one man, Stephen Bush, dead, shot by one of the soldiers. The soldiers and constables were withdrawn, the next morning the mob returned. Charles Pinney now had to escape across the roofs as this time the rioters forced their way into the Mansion House and looted the cellars of the store of wine held there. The soldiers returned but without orders to fire on the crowd could do nothing. By the end of the day the Mansion House, Excise Office, Custom House and the houses on the north and west sides of the Square were looted and on fire. There is a particularly horrific story that whilst rioters were plundering these buildings others were busy setting them on fire. The lead on the roofs was melting and running down the gutters. Several rioters were reported as being burnt alive by being trapped on the roofs while the roofs themselves were melting around them. Others jumped from the burning buildings and were impaled on the iron railings surrounding them. The flames were so great that they could be seen across the Bristol Channel in Wales.

One enterprising thief, John Ives, removed a silver basin from the Mansion House. It happened to be one the oldest pieces in the civic collection and dated from 1595. He cut it up and later offered 169 pieces of it to a local silversmith, Robert Williams. Williams informed the authorities and Ives was later transported for 14 years. Meanwhile, Williams set about repairing the basin. Two pieces were missing and had to be remade, a silver plate was added to the back to hold the artifact together.

Made by John Brodie, the 1595 rose-water ewer and basin.

Stolen and cut into pieces by John Ives.

Repaired by Robert Williams.

Image from "Civic Treasures of Bristol" by Mary E. Williams (City of Bristol, 1984, ISBN 0900199245)

While Queen Square was being destroyed, other rioters broke into Bridewell and released the prisoners before setting the building ablaze. The prison at Lawford's Gate and the New gaol suffered the same fate. At the New gaol it took the rioters three-quarters of an hour to batter a hole big enough for a boy to get through and draw back the bolts. Around 170 prisoners were released who discarded their prison clothes and joined the mob. The gallows was thrown into the New Cut. Around 20 of the 3rd Dragoon Guards arrived led by a Cornet named Kelson. They watched the crowd for a few minutes, turned about and headed back to College Green. Faced with a crowd of several thousands there wasn't a lot else they could do.

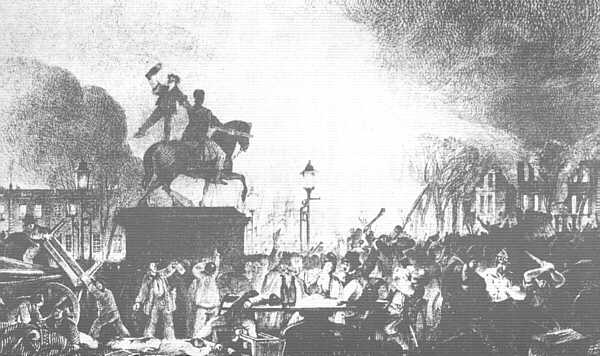

Rioters in Queen Square

Bishop Gray had also opposed the Reform Bill in the House of Lords and so the Bishops Palace near the Cathedral was attacked. Bishop Gray had received warning that this might happen and had left for Stapleton. His servants and the city constables held back the rioters for a time by using their batons freely, but when Brereton arrived he ordered them to desist, saying "if the striking continued he would ride the constables down". The mob calmed down and Brereton then withdrew his troops. The inevitable happened and the palace was burnt to the ground.

The crowd then turned their attention to the Chapter House where many valuable books and documents were stored. These were all heaped onto the floor and burnt. The main Cathedral building was also broken into but the Sub Sacrist, a brave man named Phillips, with an iron bar in his hands persuaded the mob to desist in the destruction of their heritage.

On Monday, 31st October, the Mayor, Charles Pinney finally gave Brereton the order to "take the most vigorous, effective and decisive measures to quell the riot." Brereton still dithered and so Major Mackworth gave the orders to attack. The soldiers swept across Queen Square cutting down the rioters.

Soldiers cutting through the rioters - Monday, 31st October 1831

Over 250 people suffered as a result of this charge, many of them being killed. The 14th Dragoons were recalled from Keynsham where they had been sent on the Sunday morning as the sight of them infuriated the mob so much, and reinforcements arrived from Gloucester. By now hundreds of soldiers were on their way to Bristol under the command of General Sir Richard Jackson, and the rioters dispersed. It is reckoned that somewhere between 5 and 10 thousand people were involved in the rioting and that it had left 500 people dead. Brereton was court-martialed, but on the fourth day shot himself. The Mayor, Charles Pinney, was acquitted at his trial for neglect of duty. Five rioters were sentenced to be hanged, but one was reprieved on the grounds that he was mentally deficient. Eighty-eight others were transported or imprisoned. The hangings took place above the gate of the Old Gaol on the New Cut.

The Old Gaol, The Cut, Bedminster

The Reform Bill became law in 1832. Fifty-six Rotten Boroughs were deprived of their status. The new towns were properly represented in Parliament. The vote was given to householders who paid more than £10 rental in towns or £40 in the country.

In 1835 the Municipal Corporation Act changed the constitution of the City Councils, and they stopped being the "Gentleman's Clubs" that they were. Bristol was still represented by two members until 1885 when it was increased to four and then later to six.

This page created 1st October 2000, last modified 18th August 2018