As a port Bristol always suffered from a major disadvantage - its six miles inland!!

The city has been a port ever since it existed, but improvements were needed and major work started in the 13th century. In the 1240s, part of the marsh was purchased from the Augustinian friary through which a new channel was dug for the River Frome to improve access to the River Avon. A new Bristol bridge was constructed and later in the century, an expansion of the defences known as the Port Wall. Excavations suggest it was the Redcliffe bank of the Avon which saw the most intensive development. King Henry II (1133-1189) allowed cities like Bristol to levy taxes to pay for the repair and maintenance of the ports.

The approach to the city from the sea was from the Kingroad at Avonmouth and through the tortuous River Avon. In 1662, the City Corporation decreed that because of the number of ships grounding in the Avon that no ship over 60 tons could attempt the passage under penalty of £10. Even up until the 18th century ships were often unloaded by waiting until they were beached at low tide and carrying the goods ashore. This put undue stress on the ships and many of the hulls were strained or damaged.

This helped give rise to the expression "shipshape and Bristol fashion". Shipshape was first used in the 17th century, and the Bristol fashion part was added in the early 19th century. Ships have been beached and laid on their side for repairs, called "careening" or "heaving down", for centuries. So, the expression "shipshape and Bristol fashion" could refer to a stoutly built ship capable of such treatment.

It could also mean that everything had to be stowed properly, in Bristol fashion, else it was going to end up being broken or damaged when the ship was careened in the harbour.

Sea Mills

The Romans built a harbour at Sea Mills, named Abona or Portus Abonae. The harbour was built here because this was the last point on the River Avon that ships of the day could remain afloat at low tide, and it was a handy place to provision the Centurians that were struggling with the Welsh. It was abandoned in the 4th centrury, but in 1712, Joshua Franklyn, a wealthy Bristolian, provided the money for a new wet dock and the Sea Mills Dock Company which was founded in 1716. The dock was completed in 1715, and had an area of around 9,000 square yards. This dock had one major disadvantage, the road to Bristol was practically non-existant. From its opening until around 1763 it was used to refit privateers and a whaling company used it between 1750 and 1761, but very little in the way of cargo was ever unloaded here.

Sea Mills ~ 1844

Oil on canvas by Joseph Walter (1783 - 1856)

By the time this scene was painted the docks at Sea Mills were already long past their heyday

The building of Champion's Wet Dock, later known as Merchants Dock, at Hotwells in 1768 meant the end of the Sea Mills dock and nowadays all that's left are the remains of the outer walls.

In the above photos, taken in March 2000, the remains of the harbour walls date from the the 18th century harbour, not the earlier Roman one.

Floating Harbour

Broad Quay ~ Late 18th century

This oil on canvas, attributed to Philip Vandyke, shows Broad Quay looking towards St Michaels Hill

The picture clearly shows the sleds (bottom right) that were used in place of carts.

On the Bristol side of Sea Mills is a very tight bend in the river, this bend, Horseshoe Bend, meant that ships over 300 feet long could not get round it. There were plans to straighten it but by then the entrance lock to the Floating Harbour had been built. This was only 350 feet long and so the plans for straightening the river were dropped.

The City began losing trade to Liverpool but the merchants were unwilling to invest in the docks. In 1802, William Jessop put forward a scheme to reverse the fortunes of the port. The plan was to turn the rivers Avon and Frome from Hotwells to Totterdown into a vast floating harbour. The area covered by the harbour would be around 70 acres. Ships would enter the harbour via a lock at Hotwells, behind which would be an open area of water called Cumberland Basin. Parliament approved the plans and work started in 1803. The work was estimated to cost £300,000, but by the time the work was finished in 1809, around £580,000 had been spent.

Besides the locks at Hotwells and the digging of Cumberland Basin a great deal of other work had to be done. A dam was built at Totterdown, the river Avon had to be diverted along a channel that had to dug from the dam to Hotwells, this channel is known as the New Cut and is a little under 2 miles long. A common idea is that French prisoners of war from Napoleons armies were used to dig this channel, but I can't find any evidence of this, the work being done by navvies. Another canal was built from the dam to the River Avon at St. Annes, this is the Feeder Canal whch is 1.5 miles long. That's 3.5 miles of waterway - all dug by man-power, let alone what was dug out to create the harbour. The purpose of the Feeder Canal was, and is, to both provide access for the barges heading from Bristol upstream to Bath and as a source of water to maintain the level in the Floating Harbour.

The improved docks should have been a boon for the city, but many members of the City Council were also members of the Merchant Venturers Society or the Docks Company, some were members of all three organisations. This obviously created a conflict of interest as everyone wanted the money they had invested in the Docks Company repaid, and repaid as quickly as possible with profits. The way they chose to do this was to increase the rates charged on the new docks. The charges became so high thay many companies stopped using the docks preferring to land goods at ports such as Liverpool where the rates were much lower, which was the very reason the docks were built in the first place. Many Bristol traders even transported goods overland or by inland barge to the docks at Liverpool rather than pay the rates imposed on them for using the port at Bristol.

Wine attracting a charge of £1 14s at Liverpool was charged at £3 in Bristol, silk which paid £1 18s at Liverpool was charged at £8 9s 7 1/2d at the Bristol docks.

If you thought that smugglers dealt just dealt in gold, diamonds, spirits and tobacco then you should read the following article, it appeared in Felix Farley's Bristol Journal, dated Saturday 31st July 1841.

Seizure of smuggled goods

Mr Morris, tide-surveyor and Mr Downing, assistant officer of excise at this port, two active, expert, long experienced and tried officers, have lately succeed in making two extensive seizures of smuggled soap. On the 10th inst. in the course of their duty they went on board the Queen steamer from Cork, and discovered concealed in three of the egg boxes 459lbs of Irish hard soap. On the 21st, they rummaged out in a similar manner from the Victory 312lbs of soap all consigned to one individual in Bristol, and shipped as eggs.

Due to the work of John Wesley and others in Bristol, when the slave trade was abolished in 1807 it was already in decline here and as such didn't affect Bristol much. In 1833, the slaves were emancipated in the West Indies and that was a severe blow to the port. The freeing of the slaves caused the collapse of the sugar industry in the West Indies. Plantations in Jamaica were abandoned, the price of raw sugar rose and the refineries in Bristol went into decline. In 1830, 63% of Bristol's trade was with the West Indies, by 1840 it was down to 40%, in 1871 it was 29% and by 1890 there was nothing left.

In 1835, the Municipal Corporation Act changed the constitution of the City Councils. The new Council wasn't quite so cosy with the Docks Company and started a campaign against its methods of raising revenue. By 1848, it had had enough, bought the Docks Company and started on a series of changes, improvements and repairs. The rates were reduced and trade through the port increased. In 1865 and 1870 there was enough money coming in to improve the docks still further, and in these years new locks were installed at Cumberland Basin and better transit sheds, hydraulic cranes and granaries were built.

By now ships were getting bigger and bigger and the age old problem of what to do about the approach to the city docks had to be faced once and for all. In 1867, when the old Hotwells pump was demolished Hotwell Point, a promontory into the river, was also removed but this wasn't enough. The Council had a choice, either improve the course of the River Avon or build new docks at the mouth of the river. One plan was to intall dams and locks at the mouth of the river and turn the whole of the Avon into a vast floating harbour but this was very impractical. The cost of improving navigation up the Avon was calculated as being four times as much as building a new dock, and so in 1877 the new docks at Avonmouth were opened. In 1879, another new dock was opened at Portishead, both were linked to Bristol by railway and so all three docks were in competition with eachother. In 1884, control of all three docks was in the Corporation's hands and improvements made to all of them. In 1908, the Royal Edward Dock was opened at Avonmouth and later improvements made this the best of the three.

During World War I, Bristol moved vast amounts of men and material through its ports. In 1928, new grain elevators were intalled at Avonmouth and suction equipment to unload grain ships as fast as possible. New oil and petrol storage facilities were built and in 1941 the Royal Edward Dock was enlarged. Since the 1930's Avonmouth has been, and still is, a major industrial centre.

During World War II, the ports became targets for heavy bombing, the City docks more than Avonmouth or Portishead, but these ports were badly needed, especially the ones capable of unloading oil and petrol at Avonmouth. These became so important that pipes were laid to carry the oil straight to London and other parts of the country. For twenty years after the war, trade at Avonmouth continued to increase but the City docks were in decline, the bigger ships were no longer able to navigate the Avon, even if they wanted to.

In 1965, the Brunel Way road system with its Plimsoll Bridge swing bridge over both the original locks to Cumberland Basin was opened. Now it is nearing the end of its useful life and there have been various plans to redesign the system since 2015.

Towards the city from Clifton Suspension Bridge

The above photo shows the lower entrance to the old Clifton Rocks Railway (bottom left), and the abandoned wharfs at Hotwells. In front of the large brick Bond Tobacco Warehouses is the Brunel Way road system with the Plimsoll Bridge swing bridge. In front of that are the locks into Cumberland Basin and the Floating Harbour. This was the original course of the River Avon, which now continues on through the New Cut to the right of the warehouses.

The Locks

The locks have their own story, and it's a tale of how Bristol nearly lost part of it's heritage.

The Floating Harbour was designed by William Jessop (1745-1814) and opened in 1809. There were two locks at the entrance to it entered from the River Avon. The north lock, left from the river, is now known as Howard’s Lock is 45t wide and the south lock, known as Brunel's Lock was 35ft wide. In 1844, the Bristol Dock Company commissioned Isambard Kingdom Brunel to replace the south lock. In 1848 the City Council bought the Dock Company and the following year commissioned Brunel to build a swing bridge over the south lock.

In 1863, the city ordered a swing bridge be built over the north lock. It was designed by Thomas Howard (1816-1896), the city docks engineer, and was built by Hennet, Spink and Else of Bridgwater.

By this time the locks were proving too small for a lot of ships and in 1868, Howard designed a new north lock. The bridge over the lock, being just 5 years old, was removed and put over the over the entrance to Bathurst Basin. That bridge has long gone and replaced with another.

In 1872, the original Brunel bridge over the south lock was adapted by cutting 10ft off it and moved to over the north lock. In 1874, the new north lock was opened and the south lock closed for good. In 1875, a new bridge was built by Edward Finch & Co. Ltd., of Chepstow and put over the south lock. It was originally a swing bridge as well, but sometime in the 1880s was changed to a fixed bridge. It resembled the design of Brunel's original south lock bridge and so became known as the Replica Bridge.

The now dammed Brunel's Lock (south lock) with the Replica Bridge over the top of it. Over that is the Plimsoll Bridge

Cumberland Basin from the Replica Bridge

The Plimsoll Bridge was built in 1965, and in 1968, Brunel's bridge over the north lock was removed and placed on the quay between the locks next to the north lock. There were plans to scrap the bridge, but in 1972, it was Grade II listed, but by 2011, was on the Heritage at Risk Register. The bridge was never quite forgotten and restoration work was started in 2015. This bridge, built in 1844, is older than the Clifton Suspension Bridge (1864) and is the earliest known of Brunel's tubular bridges.

The locks and dam at the entrance to Cumberland Basin are tall, and they need to be. The River Avon at 49ft, has the second highest tidal range in the world. The highest is at the Bay of Fundy in Canada which is 52 ft.

Commercial Decline

In the 1960's Britain needed new deep water ports and in 1964, the Council proposed the building of a new dock at Portbury. After this was rejected a new plan was advanced in 1967, this too was rejected. In 1971, the original Portbury plan was revised and work started in May 1972.

Royal Portbury Dock was estimated to need £15 million to complete, the final amount actually spent was £37 million, but the port is now very busy being used, amongst other things, for the import of cars. Another advantage for it is that it can handle ships three times the size that can enter Avonmouth.

By the 1980's the last ships to use the port of Bristol commercially were gone. The docks took on a new life as the developers moved in and converted many of the old warehouses into exclusive apartments and studio flats. For a while it looked as if the only people who were going to be able to enjoy the docks were the well off but, for all its faults, the Council has ensured that the old docks are open to all.

The Sand Sapphire - Hotwells - December 30, 1980

The Sand Diamond, Hotwells - December 30, 1980

I didn't realise it at the time I toook the photos, but this sand company was to be the last company using the City docks commercially. Within a very short time these too were gone.

Revival

The Council tried hard to attract new users to the docks. The Grand Prix boat racing was held in the City docks for 19 years from 1972 to 1991. These photos were taken on June 6, 1981

Unfortunately the docks are too narrow for this type of racing and the dock walls very unforgiving of anything that crashes at speed into them. After several fatal accidents the Grand Prix racing was stopped.

The old steam crane mount, Hannover Quay in 1989

The stone tower is the base of a steam crane on Hannover Quay, originally called Liverpool Wharf. It was built in 1891 by A. Chaplin & Company of Glasgow and was scrapped in 1969. The weather vane and turret were rescued from a demolished building elsewhere in the city and placed here in the 1970s. This area has seen a lot of redevelopment over the years. In 1886, it was a timber yard; 1903, a marble works. In 1922, a large bonded-warehouse, No. 29 Bond, for Tobacco Bonds Ltd. was built behind the crane, that was demolished in 1988.

This picture was taken 20 years later.

The tower is still there, but the background has changed completely - as it has many times before. The building is the Lloyds TSB bank headquarters which was built in 1993. The @ Bristol centre is to the right of this building. With the decline of the docks, many companies were given incentives to move to Bristol, this and the rising costs of being based in London led many businesses to move to Bristol. You might notice the tower is on a square plinth. The top of that was the original height of the quay before it was lowered during the redevelopment of the site.

Canon's Marsh from Cabot Tower, February 2000

The photo shows the Bristol Industrial Museum, @Bristol and the LLoyds TSB bank headquarters buildings

The red and cream buildings in the background of the above photos were the Bristol Industrial Museum on Princes Wharf. The museum was opened in 1974 but closed on October 29, 2006, a very sad loss. A new museum in the same transit sheds was opened in June 2011 and known as The M Shed which contains many of the original exhibits from the old museum. It's always worth a visit as it displays a lot of Bristol's history.

In front of the museum are shown 3 of the 4 remaining dockside electric cranes. The cranes were all built by Stothert & Pitt of Bath. In the 1950's, there were 8 of the cranes on this wharf alone with over 40 in the docks.

A view of the docks showing Cabot Tower, @Bristol, the cathedral and the Wills University Tower

Redevelopment of the old warehouses on Redcliffe Wharf into shops and flats, giving them a new lease of life.

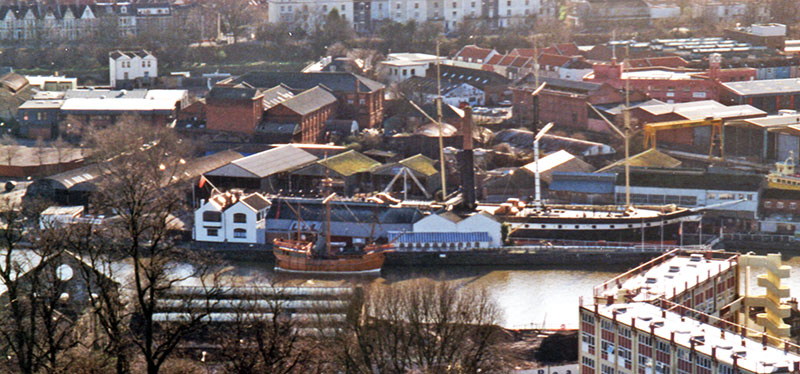

Towards the Hotwells end of the docks is the Bristol Maritime Museum, home of the SS Great Britain and the replica of Cabot's Matthew.

These photos were taken in February, 2000.

The docks have seen tremendous changes over the years, but has always rewarded a walk around the area...

Sources & Resources

Bristol City Docks

Bristol Cranes by Thomas Rasche

Bristol Floating Harbour

Bristol Industrial Museum Remembered - A fascinating look at the exhibits from the original Bristol Industrial Museum

Brunel Swing Bridge - Engineering Timelines

Brunel's Other Bridge

Careening - Wikipedia

Cumberland Basin Bridges - Grace's Guide

Dockside Cranes - BBC Bristol

History of Racing in Bristol's Floating Harbout - Fast on Water

Shipshape and Bristol Fashion - Word Histories

Urban Infrastructure by Gareth Dean from The Oxford Handbook of Later Medieval Archaeology in Britain

Waterways of Bristol - Jeffery Knaggs - Walks around the various Bristol waterways